Volume 39, Issue 1 ⦁ Pages: 99-109

Abstract

Studies have focused on the effects of chronic alcohol consumption and the mechanisms of tissue injury underlying alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, with less focus on the pathophysiological consequences of binge alcohol consumption. Alcohol binge drinking prevalence continues to rise, particularly among individuals ages 18 to 24. However, it is also frequent in individuals ages 65 and older. High blood alcohol levels achieved with this pattern of alcohol consumption are of particular concern, as alcohol can permeate to virtually all tissues in the body, resulting in significant alterations in organ function, which leads to multisystemic pathophysiological consequences. In addition to the pattern, amount, and frequency of alcohol consumption, additional factors, including the type of alcoholic beverage, may contribute differentially to the risk for alcohol-induced tissue injury. Preclinical and translational research strategies are needed to enhance our understanding of the effects of binge alcohol drinking, particularly for individuals with a history of chronic alcohol consumption. Identification of underlying pathophysiological processes responsible for tissue and organ injury can lead to development of preventive or therapeutic interventions to reduce the health care burden associated with binge alcohol drinking.

Introduction

Alcohol misuse is the fifth-leading risk factor for premature death and disability worldwide,1 and, adjusting for age, alcohol is the leading risk factor for mortality and the overall burden of disease in the 15 to 59 age group.2 According to the World Health Organization, in 2004, 4.5% of the global burden of disease and injury was attributable to alcohol: 7.4% for men and 1.4% for women.2

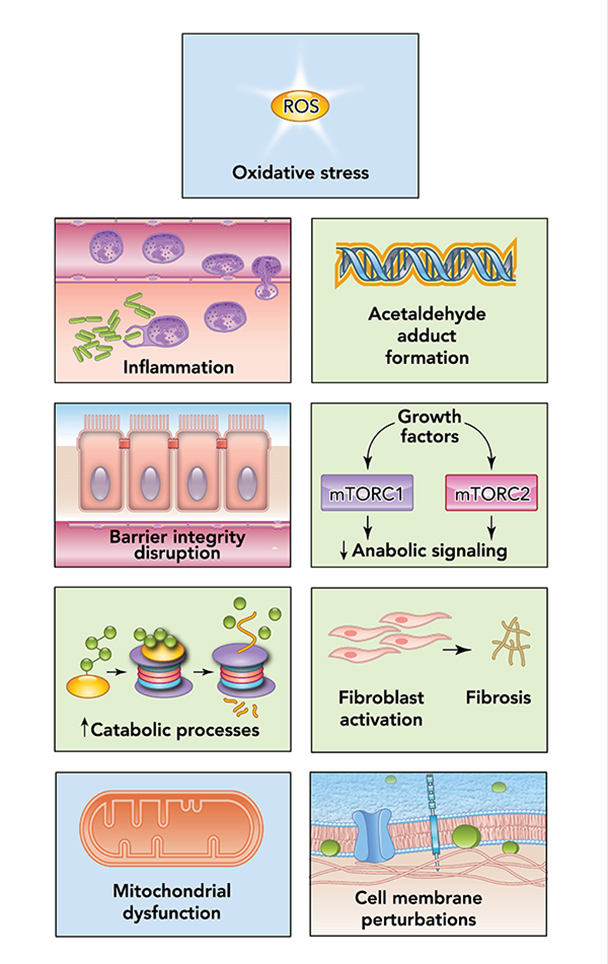

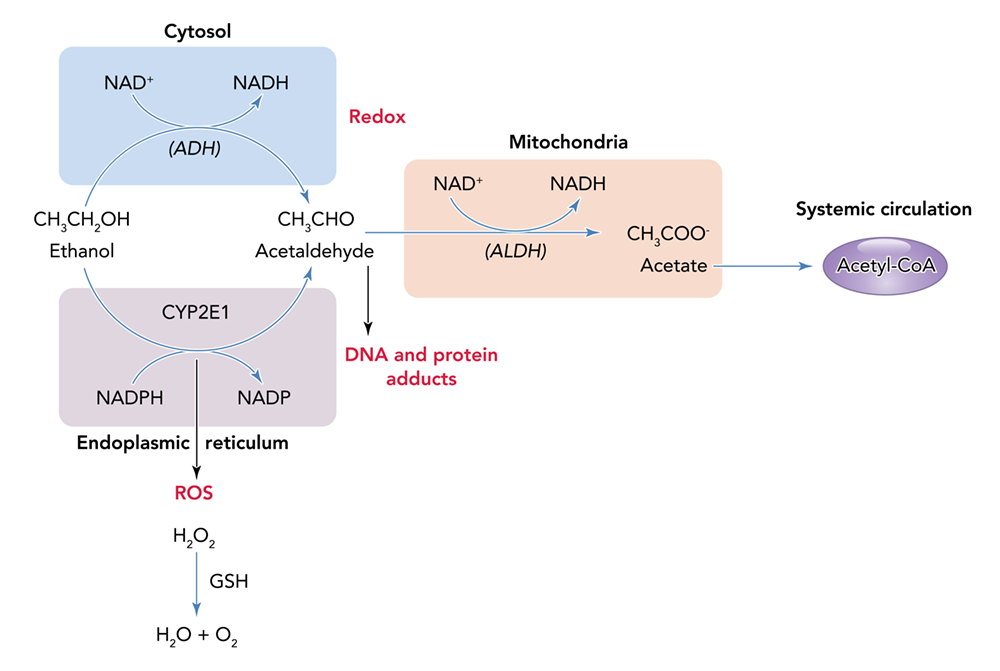

Alcohol can permeate to virtually all tissues in the body, resulting in significant alterations in organ function, which leads to multisystemic pathophysiological consequences. The effect of alcohol misuse on multiple organ systems outside the liver, mediated through direct and indirect effects beyond those associated with alterations in the nutritional state of the individual, has been well-established.3,4 The resulting tissue injury has increasingly been recognized and examined as a contributing factor to alcohol-related comorbidities and mortality. Several pathophysiological mechanisms have been identified as causative factors of tissue and organ injuries that resulted from excessive alcohol consumption, including acetaldehyde generation, adduct formation, mitochondrial injury, cell membrane perturbations, immune modulation, and oxidative stress (Figure 1). Some of these mechanisms are the result of direct alcohol-induced cell perturbations, whereas others are the consequence of tissue alcohol metabolism (Figure 2). The oxidative stress caused by excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or a reduction in reducing antioxidant equivalents in tissue has been consistently demonstrated to be an overall mechanism of the tissue injury that results from chronic alcohol misuse. Dose-dependent relationships between alcohol consumption and incidence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, dysrhythmias, stroke, pneumonia, and fetal alcohol syndrome have been reported.4 However, recognition of alcohol as an underlying causal factor in comorbid conditions remains a challenge in the clinical setting.

Several factors associated with alcohol consumption, including pattern, amount, and frequency, and the type of alcoholic beverage, may contribute differentially to the risk for alcohol-induced tissue injury. The question of whether all types of alcohol produce similar pathophysiological consequences remains to be answered. However, the particularly detrimental effects of binge drinking have increasingly gained attention. Binge drinking, as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), is a pattern of alcohol consumption that brings blood alcohol concentration to .08 g/dL, which typically occurs following the intake of five or more standard alcohol drinks by men and four or more by women over a period of approximately 2 hours.5 Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health show overall prevalence of binge drinking (during the past 30 days) of 26.9% among U.S. adults ages 18 and older.6 Those data show that binge drinking prevalence and intensity are highest among those ages 18 to 24 but also occur in high frequency among older individuals (ages 65 and older). Thus, binge drinking prevails in two vulnerable segments of the population, raising their risks for greater severity of injury and frequency of comorbidities.

Understanding the Biomedical Consequences of Binge Drinking

A limitation to our understanding of the consequences of binge alcohol consumption on organ injury is the lack of information on the time period, duration, and number of binge occurrences that describe the long-term practice of binge drinking. Preclinical studies conducted under controlled conditions provide opportunities to examine quantity and frequency variables in the investigation of the effects of alcohol consumption on organ injuries. However, interpreting, comparing, and integrating the patterns of alcohol consumption described in clinical reports is difficult because of the different types of data collected across studies. This difficulty underscores the need for researchers to perform more rigorous comprehensive and systematic data collection on alcohol use patterns. The Timeline Followback (TLFB) tool, for example, uses a calendar and a structured interview to collect retrospective information on the types and frequency of alcohol use over a given time period.7,8 Nevertheless, accounting for a lifetime pattern of binge alcohol consumption remains challenging when conducting clinical studies. Alcohol consumption patterns should be taken into consideration for future development of alcohol use screening tools, because binge drinking has been suggested to result in greater alcohol-related harm.9

Different types of alcoholic beverages consumed in binge drinking episodes could also differentially affect the health consequences associated with binge drinking. Epidemiological studies that compared the prevalence of coronary heart disease in “wine-drinking countries” and beer- or liquor-drinking countries have proposed that red wine, but not beer or spirits, consumed with a meal may confer cardiovascular protection.10 The proposed protective effects of red wine include decreased blood clot formation, vascular relaxation, and attenuation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or bad cholesterol) oxidation, an early event preceding formation of cholesterol-filled plaque. These effects are attributed to polyphenols, especially resveratrol, and their antioxidant properties.

However, not all reports support the link between consuming a specific beverage type (i.e., wine vs. beer or spirits) and health benefits. Some reports suggest that beverage amount is more directly linked to health outcomes.11,12 The differential contribution of alcoholic beverages to beneficial or detrimental health outcomes remains to be examined in both preclinical and clinical studies. In binge drinking episodes, the form of alcohol consumed most frequently is beer (67.1%), followed by liquor (21.9%) and wine (10.9%).13 Moreover, beer accounts for most of the alcohol consumed by drinkers who are at the highest risk of causing or incurring alcohol-related harm, including drinkers ages 18 to 20, those with more frequent binge episodes per month, and those drinking 8 or more drinks per binge episode. Therefore, dissecting how pattern of drinking and type of alcoholic beverage contribute to overall outcomes is challenging.

The Gastrointestinal Tract, Liver, and Pancreas

Of all tissues affected by binge-like alcohol consumption, the gastrointestinal tract bears the greatest burden due to its direct exposure to high tissue concentrations of alcohol following ingestion (Figure 3). Binge drinking often occurs apart from meals, which may also contribute to its deleterious effects on organs. Food consumed at the time of alcohol consumption influences not only the alcohol absorption rate and blood alcohol concentration, but also the direct effect of alcohol on the gastrointestinal mucosa. Hence, binge drinking is more likely to contribute to organ injury than paced, moderate alcohol drinking that is associated with a meal.

Image

| Image

| Image

| Image

| Image

|

Gastrointestinal tract, liver, and pancreas

| Cardiovascular system

| Pulmonary system

| Musculoskeletal system

| Nervous system

|

Figure 3 The systemic effects of chronic binge alcohol consumption and the principal organ systems affected.

The gut mucosa is particularly susceptible to alcohol-induced injury, and alcohol consumption can result in a loss of intestinal barrier integrity. Several direct and indirect mechanisms have been identified that disrupt the structural and functional components involved in maintaining the integrity of the gut mucosal barrier. Alcohol and its breakdown products directly damage epithelial cells through generation of ROS and through disruption of tight junction protein expression and signaling.14 This process disrupts the integrity of the intestinal barrier, allowing bacteria and toxins to reach the bloodstream. Acute alcohol binge drinking in healthy human volunteers can produce a significant increase in serum endotoxin levels and bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA, suggesting the gastrointestinal microbial origin of endotoxin.15-17

More recently, attention has focused on the changes in intestinal microbiome that contribute to alcohol-associated intestinal inflammation and permeability. Alcohol promotes both dysbiosis (decreased diversity or an imbalance in the types of microbes) and bacterial overgrowth in the gastrointestinal system.18-21 Alcohol alters the balance between bacterial strains, decreasing the presence of beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and increasing that of Proteobacteria and Bacilli.19 This imbalance adds to the possibility that bacterial overgrowth may contribute to local mucosal inflammation through bacterial metabolism of alcohol and enhanced local production of metabolites such as acetaldehyde.22 Moreover, increased bacterial load, together with shifts in intestinal bacterial strains, brings about diverse profiles of bacterial-derived metabolites.

How these shifts in bacterial strains, load, and metabolites contribute to organ injury remains to be fully elucidated. However, it is reasonable to speculate that greater bacterial burden and altered bacterial profiles, together with increased permeability of the gut mucosa, would lead to continuous entry of bacterial toxins into the systemic circulation. These changes could produce chronic and sustained activation of immune responses that, in turn, could lead to immune exhaustion and dysfunction. Preclinical studies show that binge-on-chronic alcohol feeding alters the gut microflora at multiple taxonomic levels, influencing hepatic inflammation, neutrophil infiltration, and liver steatosis,23 which highlights the need for clinical investigation into the relationship between gut microflora and hepatic liver disease.

Local and Systemic Consequences of Gut Injury

Toxins and bacterial products leaked from the gastrointestinal tract can be transported through the lymphatic system. This route of dissemination, which escapes hepatic clearance, may prove critical in the enhanced systemic delivery of toxins. Preclinical studies have shown that repeated binge-like alcohol intoxication increases lymphatic permeability and inflammation in the adipose tissue that immediately surrounds the mesenteric lymphatics. Inflammatory response in mesenteric perilymphatic adipose tissue is associated with altered adipose tissue insulin signaling and circulating adipokine profiles, which suggests a link between lymphatic leak, adipose tissue inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation.24

Whether chronic alcohol consumption not in a binge pattern produces similar alterations in lymphatic permeability and mesenteric adipose inflammation remains to be determined. However, localized alterations in mesenteric adipose tissue metabolic regulation, including insulin signaling, may prove to be relevant to the enhanced risk for metabolic syndrome that is associated with binge alcohol consumption.25 After burn injury and a binge-like pattern of alcohol intoxication, rodents showed similar exacerbation of adipose tissue inflammation.26 This suggests that a possible synergism between binge-like alcohol intoxication and injury promotes a dysregulated adipose environment conducive to insulin resistance, and potentially metabolic syndrome, if these alterations are sustained beyond the immediate period following binge drinking or burn injury.3

Second to the gastrointestinal tract, the liver has the most exposure to high alcohol concentrations during periods of binge drinking. Hepatocellular metabolism of alcohol and the resulting ROS generation; acetaldehyde formation and the resulting adducts; immune response activation, particularly in Kupffer and stellate cells; and alterations in cell signaling are all proposed as mechanisms that underlie liver injury associated with binge-like alcohol consumption. For people with chronic alcoholism, binge drinking augments liver injury27,28 and is a major trigger for the progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis.29-31 In one study, rodents that received binge-on-chronic alcohol exposure had accentuated elevation in liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase), hepatic steatosis, and inflammatory cytokine expression compared to rodents subjected only to chronic or to acute alcohol exposure.32 These results demonstrate that binge-on-chronic alcohol exposure results in greater insult than either chronic or acute alcohol exposure alone. Clinical studies have provided evidence of associations among alcohol binge drinking patterns, immune activation (high CD69 and low TLR4, CXCR4, and CCR2 expression), and decreased chemotactic responses to SDF-1 and MCP-1.33 These associations reflect an altered immune profile that may be associated with liver injury and increased susceptibility to infection. More recently, attention has been drawn to the potential greater liver injury in individuals with metabolic syndrome. A population-based study showed a direct association between binge drinking frequency and liver disease risk, after adjusting for average daily alcohol intake and age.34 In this study, binge drinking and metabolic syndrome produced supra-additive increases in the risk of decompensated liver disease. Because of increasing rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome, research on the effects of alcohol misuse and the biomedical consequences is needed for this particular segment of the population.

Located strategically between the liver and the gastrointestinal tract, the pancreas also has high susceptibility to alcohol-induced tissue injury. Heavy, chronic alcohol consumption is a recognized contributing factor in the development of pancreatitis. However, how dose and pattern of alcohol consumption affect pancreatic function and structure is not known. Studies show that alcohol consumption of more than 40 g per day is increasingly detrimental for any type of pancreatitis.35 Retrospective clinical studies have shown that binge alcohol drinking is associated with aggravation of first-attack severe acute pancreatitis, which is reflected in higher admission levels of serum triglycerides, Balthazar computed tomographic score, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, as well as higher mortality and incidence of complications.36

Insight into the mechanisms involved in pancreatic injury is derived from preclinical studies that show detrimental effects of binge alcohol exposure on the pancreas. These effects include tissue edema, inflammation, acinar atrophy and moderate fibrosis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, and apoptotic and necrotic cell death. These structural changes are associated with pancreatic dysfunctional changes, which are reflected by altered levels of alpha-amylase, glucose, and insulin, strongly suggesting a detrimental effect of acute binge alcohol exposure on the pancreas. Specifically, preclinical studies have proposed that, alone, chronic and binge alcohol exposure caused minimal pancreatic injury, but chronic plus binge alcohol exposure resulted in significant apoptotic cell death; alterations in alpha-amylase, glucose, and insulin; pancreatic inflammation; and protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation, which are indicative of oxidative stress.37 The pathogenesis of alcoholic pancreatitis involves acinar cell alcohol metabolism. The direct toxic effects of alcohol and its metabolites on acinar cells, in the presence of an appropriate trigger factor, may predispose the gland to injury. In addition, pancreatic stellate cells are implicated in alcoholic pancreatic fibrosis.38 Thus, experimental and clinical data suggest that alcohol consumption alone does not initiate pancreatitis, but it sensitizes the pancreas to disease from other insults, including smoking, exposure to bacterial toxins, viral infections, and binge alcohol consumption.39

Cardiovascular Consequences

The effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular function has been the subject of much debate. The relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular health is not linear and is thought to follow a J-shaped curve, with low amounts of alcohol consumption frequently reported as cardioprotective.40 However, data suggest that binge drinking is associated with transient increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Figure 3).41-43 The prevalence of hypertension has been reported to be higher in individuals who consume more than six drinks per day. However, the pattern of alcohol consumption was not considered in these studies.44 The effect of even a modest rise in blood pressure is considerable, as it is a recognized risk factor for cardiovascular mortality.45,46 Binge drinking has been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular comorbidities, including hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, and sudden death, and this risk may extend to the younger population as well.47-51 Acute elevations in blood alcohol levels resulting from binge alcohol consumption are associated with an increased risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation, a most common arrhythmia strongly associated with adverse cardiovascular events and sudden death.52 A higher risk for myocardial infarction has been reported after 1 day of heavy alcohol consumption (which could reflect a binge-like pattern of alcohol consumption).53

Few preclinical studies have examined the effect of binge drinking on cardiac function. In one study, over a 5-week period, rodents received repeated episodes of alcohol administration that modeled a binge drinking pattern.54 These rodents did not show changes in cardiac structure, but this drinking pattern resulted in increased phosphorylation of myocardial p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and transient increases in blood pressure, which became progressively higher with repeated episodes of binge drinking. These effects were partly mediated by adrenergic mechanisms. More recently, the combined binge-on-chronic pattern of alcohol feeding to rodents has been shown to result in alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy,characterized by increased myocardial oxidative/nitrative stress, impaired mitochondrial function and biogenesis, and enhanced cardiac steatosis.55,56 The role of oxidative stress has been confirmed by other preclinical studies.57

Pulmonary Consequences

Preclinical studies have identified impairments in multiple aspects of lung function after chronic and binge-like alcohol administration, including altered epithelial barrier function, suppressed immunity, impaired bacterial clearance, depleted glutathione (GSH), and impaired pulmonary epithelial ciliary function (Figure 3).58,59 Moreover, alcohol binge drinking increases the risk for sustaining traumatic injuries and aggravates outcomes from traumatic injuries,60 such as burns,26,58,61-63 bone fractures,64 and hemorrhagic shock.65 For alcohol-intoxicated hosts, similar detrimental effects have been reported on bacterial pneumonia outcomes, a frequent comorbid condition associated with traumatic injury.66 Binge-like alcohol administration impairs innate and adaptive immune responses in the lungs, thereby increasing infection susceptibility, morbidity, and mortality.61,62 It is possible that, in hosts previously exposed to chronic alcohol consumption, binge drinking detrimentally affects pulmonary outcomes from traumatic injury by priming host defense mechanisms. This combined effect may prevent clear isolation of binge alcohol consumption effects from chronic alcohol consumption effects.

Musculoskeletal Consequences

The incidence of skeletal muscle dysfunction (i.e., myopathy) resulting from chronic alcohol misuse surpasses that of cirrhosis.67 This progressive loss of lean mass is multifactorial and involves metabolic, inflammatory, and extracellular matrix alterations, which promote muscle proteolysis and decreased protein synthesis (Figure 3).68 An additional severe complication of binge drinking is the development of acute muscle injury, rhabdomyolysis. Binge drinking that precedes coma or immobility can lead to rhabdomyolysis and, consequently, to renal injury, as documented in case reports in the literature.69-71 The mechanisms are not well-understood, but they may involve acute hypokalemia.72 This phenomenon may warrant further study, as environmental factors such as high ambient temperature and individual drug-drug interactions can obscure presentation and hinder management of alcohol-induced rhabdomyolysis.

Preclinical studies suggest that, after binge-like alcohol administration, physical exercise may ameliorate cognitive impairment and suppressed neurogenesis.73 The effect of binge alcohol consumption on exercise performance and recovery remains to be systematically investigated. One clinical study reported no change in isokinetic and isometric muscle performance, central activation, or creatine kinase release during or after acute moderate alcohol intoxication.74 Short-term reductions in lower-extremity performance were reported in a study that investigated athletes after an alcohol drinking episode and the associated reduced sleep hours.75 Another study found that alcohol consumption following a simulated rugby game decreased lower-body power output but did not affect performance of tasks requiring repeated maximal muscular effort.76 However, the same researchers found that alcohol consumption following eccentric exercise accentuated the losses in dynamic and static strength in males.77

In contrast, alcohol consumption following muscle-damaging resistance exercise did not alter inflammatory capacity or muscular performance recovery in resistance-trained women,78 suggesting possible gender differences in alcohol’s modulation of exercise performance and recovery. These studies were conducted using healthy volunteers and athletes. Other studies that investigated patients with alcoholic liver disease showed lower muscular endurance, maximal voluntary isometric muscle strength, and total work of knee extensors.79 Controlled studies are needed, particularly in light of the popularity of binge drinking events frequently associated with collegiate and professional sports.

Neuropathological Consequences

The behavioral and cognitive effects of binge drinking include difficulties in decision-making and impulse control, impairments in motor skills (e.g., balance and hand-eye coordination), blackouts, and loss of consciousness (Figure 3).80 All of these effects have serious health consequences ranging from falls and injuries to death.81 In particular, adolescents are vulnerable to the cognitive manifestations and memory loss associated with binge drinking. National estimates suggest that significant numbers of people who binge drink report at least one incident of blacking out in the previous year.82,83 Blackouts, defined as short periods of amnesia during which a person actively engages in behaviors (e.g., walking or talking) without creating memories for them, often occur at blood alcohol concentrations exceeding .25 g/dL.84,85 Blackouts are common among college students who drink alcohol. Estimates suggest that up to 50% of students that engaged in drinking reported a blackout episode during the past year.86,87 The pattern of rapid consumption of large doses of alcohol, frequently on an empty stomach, is characteristic of the adolescent period.88

The consequences of binge drinking are not short-lived or limited to the period of intoxication. Imaging studies of binge drinking adolescents document long-lasting changes. Reports indicate structural changes in the prefrontal and parietal regions, as well as in regions known to mediate reward, and these changes are thought to reflect long-lasting effects of alcohol bingeing on critical neurodevelopmental processes.89 Functional imaging studies of the brains of binge drinking and nondrinking adolescents found that binge drinking adolescents showed greater responses in frontal and parietal regions, no hippocampal activation to novel word pairs, and modest decreases in word-pair recall, which could indicate disadvantaged processing of novel verbal information and a slower learning slope.90 In another study, adolescent binge drinking resulted in gender-specific differences in frontal, temporal, and cerebellar brain activation during a special working memory task, reflecting differential effects of binge drinking on neuropsychological performance and possibly greater vulnerability in female adolescents.91 Other researchers have reported that degradations in neural white matter were linked with impaired cognitive functioning in adolescents who binge drank.92

Adolescent rodent intermittent ethanol exposure that modeled human adolescent binge drinking produced a range of pathophysiological and neurobehavioral sequelae, including altered adult synapses, cognition, and sleep; reduced adult neurogenesis; increased neuroimmune gene expression; and increased adult alcohol drinking associated with disinhibition and social anxiety.93 Preclinical studies indicated that binge drinking could produce brain structural abnormalities. Binge alcohol administration to rodents produced increases in cerebrospinal fluid volume in the lateral ventricles and cisterns, decreased levels of N-acetylaspartate and total creatine, and increased choline-containing compounds, glutamate, and glutamine, all of which recovered during abstinence.94 Moreover, preclinical data suggested that adolescent binge drinking sensitized the neurocircuitry of addiction, possibly inducing abnormal plasticity in reward-related learning processes, which could contribute to adolescent vulnerability to addiction.95

Summary

Although the effects of chronic alcohol consumption and the mechanisms of tissue injury underlying alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis have received much attention, less attention has been focused on the pathophysiological consequences of binge alcohol consumption. The differential duration of the intoxication period, excessive concentrations of alcohol at the tissue level, accelerated alcohol metabolism and generation of ROS and alcohol metabolites, and acute disruption of antioxidant mechanisms are some of the salient differences between chronic and binge-like alcohol-mediated tissue injury. Because of the differences in male and female alcohol metabolism rates, it is possible that greater tissue injury is produced in females who consume alcohol in binge-like patterns. Furthermore, in an aging population already riddled with polypharmacy, there is heightened potential for toxicity during an alcohol binge (Figure 4). Also, pre-existing comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease, renal failure, or steatohepatitis may predispose binge drinkers to accelerated tissue injury.

Additional research is needed to better recognize the differential effects of binge, chronic, and binge-on-chronic patterns of alcohol consumption. Animal models that reflect these patterns of alcohol exposure are needed. In addition, greater effort toward documenting a history of alcohol consumption, including the frequency, quantity, and quality of alcoholic beverages consumed, should help us better understand the effects of binge drinking on biological systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for editorial support from Rebecca Gonzales and grant support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number P60AA009803 (LSUHSC-NO Comprehensive Alcohol–HIV/AIDS Research Center).

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.