Volume 45, Issue 1 ⦁ Article Number: 10 ⦁ https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v45.1.10

Abstract

PURPOSE: Alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (AUD) among adults age 50 and older are an expanding public health challenge, requiring effective alcohol prevention interventions. Empirical literature on prevention interventions among older adults is limited by design issues, lack of publication, and misconceptions of aging. To enhance scientific rigor, prior reviews of prevention interventions among older adults excluded pre-to-posttest studies and studies with subgroups, such as veterans, racial minorities, and individuals who seek out digital interventions. The current narrative review aims to understand with whom prevention interventions for older adults are tested; describe barriers and facilitators of successful interventions; and include perspectives of both older adults and intervention providers. Unlike prior reviews, it includes a range of study designs, including digital interventions, and examines decade of age, periods in which studies took place, and generational factors associated with prevention intervention success.

SEARCH METHODS: In December 2024, Boolean search terms, such as “alcohol*,” “older adults,” and “intervention,” were used across medical and social science databases, including PubMed, World of Science, PsycInfo, Social Sciences Citation Index, Cochrane Database, and other sources. The searches identified 983 articles published between 1999 and 2024, 582 of which were duplicates. Of the 401 abstracts reviewed, 231 did not mention older adults and/or alcohol. Thus, 170 full texts were reviewed. To be included, studies had to be peer-reviewed; have a mean participant age of 55 and older or a labeled subsample of individuals age 50 and older; focus on a nonpharmacological intervention; and reported alcohol or alcohol-related outcomes or older adult and/or provider perspectives of interventions. Studies set in a formal substance use treatment program were excluded. Overall, 84 records describing 51 interventions and 16 articles of consumer and provider perspectives were synthesized.

SEARCH RESULTS: Studies were categorized into primary prevention, secondary prevention of AUD, and tertiary prevention of worsening AUD. Most interventions were delivered in person, in primary care, with individuals born from 1901 to 1923 (Greatest Generation) and 1924 to 1945 (The Silent Generation), and yielded significant reductions in alcohol use and related consequences. Only The Silent Generation consistently responded to interventions, demonstrating large effects. Additionally, two out of 18 randomized controlled trials found that individuals born from 1946 to 1964 (Baby Boomers) significantly responded to prevention interventions. Digital interventions were successful across generations.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS: Barriers to successful interventions occur at the organizational, provider, and older adult levels. Prevention intervention facilitators include drink tracking, agreement with another person, and aligning tone of the intervention to older adult perspectives of their drinking and perceived need to change. Adapting prevention interventions to older adults could include tailoring to an individual’s identity, culture, and meaning behind their drinking, which is often defined by generation, rather than only by age.

Key Takeaways

- Older adults born from 1924 to 1945 (The Silent Generation) had strong responses to primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohol prevention interventions, particularly those that involved a physician (i.e., a physician delivered the intervention or followed up regarding alcohol use), with multiple contacts over time, and across decades of life. However, Baby Boomers did not respond as well or as consistently to the interventions.

- Intervention components that showed effectiveness across intervention types, decades of life, and generations included drink tracking, discussion with another person about alcohol, an agreement to change, and aligning the tone of the provider with the older adult’s level of concern about their own drinking.

- Digital interventions showed promise across decades of age and generations, including web- and text messaging-based interventions. This finding is important given that primary care may no longer be an ideal setting for interventions for older adults due to the high burdens placed on providers and other barriers.

- A large proportion of studies found that screening and/or assessment alone were as effective as the active interventions they were testing, particularly when screening/assessment was conducted using older adult-specific tools, such as the Alcohol-Related Problems Survey and its descendant, the Comorbidity-Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool. Other non-older adult-specific instruments that produced similar effects were the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test and the Alcohol, Smoking, Substance Involvement Test.

Introduction

As the global population ages, alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (AUD) among older adults (defined here as adults age 50 and older) present a complex and growing public health challenge. Beginning at around age 50, adults experience physiological changes to the body and brain that affect their ability to metabolize alcohol, such as loss of lean body mass and an increasingly permeable blood brain barrier.1 These and other changes lead to greater intoxication and harm at lower levels of alcohol consumption, as well as to hazardous medication interactions and diminished ability to detect impairment. According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans2 and the World Health Organization,3,4 low-risk drinking among older adults is defined as one standard drink (14 g ethanol) or less per day for women of any age and men age 65 and older, and as two standard drinks or less per day for men younger than age 65. In the United States, alcohol use among older adults has steadily increased over the past 20 years, with studies demonstrating an increase of up to 22% for binge drinking (five or more drinks for men, or four or more drinks for women, in a drinking episode5) and heavy drinking (drinking beyond low-risk guidelines5).6 Currently, 61.5% of U.S. older adults drink alcohol, 17% binge drink, 5% binge drink on five or more days in the past month, and 7% meet criteria for AUD.5 Strong associations between alcohol use in older adults and cancer, multimorbidity, hospitalizations, early nursing home entry, and mortality7 indicate that effective prevention interventions may be an important tool for addressing this public health problem.6

Alcohol-Related Prevention Interventions Among Older Adults

Given the heightened vulnerability to alcohol among older adults, what should be the goal of prevention—abstinence (i.e., no alcohol consumption), moderate drinking (e.g., drinking at recommended low-risk levels), or harm reduction (e.g., any reduction in drinking to reduce risk of health or social consequences)?7 Existing prevention interventions are tailored to settings and individuals with goals ranging from abstinence to low(er) risk drinking. Policy initiatives and public health awareness campaigns to address other public health problems (e.g., anti-tobacco and opioid awareness campaigns) aim to reach the widest audience,8,9 yet most alcohol prevention interventions occur at the individual level, such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) approaches.10 Designed for individuals whose alcohol consumption exceeds low-risk guidelines, including those with AUD, SBIRT is the predominant prevention intervention across the life span and set mainly in primary care.11 Its goal is to prevent and reduce harm across the drinking spectrum and to connect people who do not respond to the intervention to specialty treatment.12 SBIRT was disseminated in the United States via federal grants awarded to training programs, states, and academic hospitals to train providers to implement SBIRT.13 Early findings were promising,11,12,14 yet later meta-analyses found mixed results for SBIRT’s efficacy across settings, severity of alcohol use, and demographics.15,16 Additionally, there was a lack of data on SBIRT with older adults,15 and studies found an increasingly lower likelihood of alcohol screening as individuals aged.17-20 Subsequent grants were awarded to providers focusing on older adults,10 and SBIRT was adapted for older adults primarily by adding an age-specific health workbook21 for patients and providers to guide interventions. These initiatives have served thousands of older adults,10 yet their evaluation has been limited. Outcome data were not collected consistently; interventions were vaguely described; few studies used fidelity measures or reported intervention dosage; the effectiveness of individual components of the prevention interventions was rarely examined; and findings were often not peer-reviewed or published. When findings were reported, they often were limited to small subsamples and pre-to-posttest effects only, obfuscating older adult prevention intervention effectiveness.22,23

Limitations of Prior Reviews of Prevention Interventions for Older Adults

Five systematic reviews24-28 have evaluated prevention interventions for alcohol use among older adults, and a sixth systematic review focused on digital alcohol interventions assessed age (i.e., age 55 and older) as a moderator.29 These reviews concluded that prevention interventions provide a potential for reduced harm among older adults; however, the investigators hesitated to draw definitive conclusions given unclear intervention descriptions,24,26 an absence of rigorous research design,25-28 and inconsistent outcomes24 within and across studies. To enhance methodological rigor, the reviews also excluded a substantial proportion of the empirical literature, such as pre-to-posttest designs and program evaluations, and key subgroups of older adults (i.e., veterans, inpatients, and racial/ethnic minorities),28 limiting generalizability. Other than the meta-analysis29 of digital interventions, which found that adults age 55 and older were 66% more likely to respond to online treatment compared to younger adults, no review included digital interventions.

In addition, none of the reviews above addressed potential generational effects on prevention interventions for older adults, despite the fact that generational cohort has often been cited as the primary cause of the dramatic increase in alcohol use among older adults described above.6,30 In 2025, adults ages 50 and older span multiple generations, The Silent Generation (TSG, which comprises individuals born from 1924 to 1945 who are now ages 80 to 101), Baby Boomers (BBs, born from 1946 to 1964, who are now ages 61 to 79), and Generation X (Gen X, born from 1965 to 1980, who are now ages 45 to 60). While alcohol remains the most used substance across older adult cohorts,5 each generation has experienced distinct historical and cultural contexts that have and continue to influence alcohol use after age 50. For example, average daily alcohol consumption decreased for the first part of the 20th century, with data showing that 50% of males from the Greatest Generation (GG, individuals born from 1901 to 1923) who drank reduced their consumption to moderate drinking (24 g of alcohol or less per day) starting around age 58, whereas in the following generation, TSG, this reduction occurred by age 46.31 Born during alcohol prohibition and temperance movements in the United States, TSG individuals eschewed heavy drinking and tended to view alcohol use as immoral.32,33 In contrast, alcohol use increased again among older adults as BBs began turning 50 in 1996.34,35 Characterized as a rebellious generation, BBs enjoyed greater access to and permissive attitudes toward drugs and alcohol with longer life expectancies, leading to at-risk drinking (i.e., drinking beyond low-risk guidelines) into their 60s and beyond.7

Age effects (i.e., where a particular age range or decade of life causes differential responses to interventions), period effects (i.e., when a particular era influences people across all age groups), and generation effects (i.e., a particular cohort of individuals born in a particular period) may all differentially influence preferences for and responses to prevention interventions. Generally, research to date mostly has assumed that aging/age, and its concomitant life events and physiological developments, is the most important factor in defining older adults as a group when tailoring interventions. Period effects likely also influence intervention preferences, such as the occurrence of a pandemic that necessitates remote health care as a new treatment and prevention approach; however, period effects can be difficult to parse out, especially in the absence of data across several decades. In contrast, generational effects are easier to identify and can address contextual factors of individuals born in a particular era. For example, Gen X, who began entering their 50s in 2015,36 is the first generation to grow up with computers and may be more receptive to digital prevention interventions compared to prior generations. Since generation is relatively unexplored as a factor in prevention interventions for older adults, an examination of if and/or how generation influences responses to alcohol prevention interventions is justified.

The Current Study

This narrative review synthesizes literature on alcohol-related prevention interventions among older adults. It aims to understand how and with whom older adult prevention interventions have been tested, describe barriers and facilitators of successful prevention interventions, and collect older adult and provider perspectives to identify potential intervention adaptations in the future. It differs from previous reviews by: (1) including qualitative studies, pre-to-posttest designs, and quasi-comparison designs, in addition to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to understand the state of prevention intervention research in older adults; (2) including digital interventions; and (3) examining studies in their historical context by investigating the generation(s) included and the years during which data were collected.

Methods

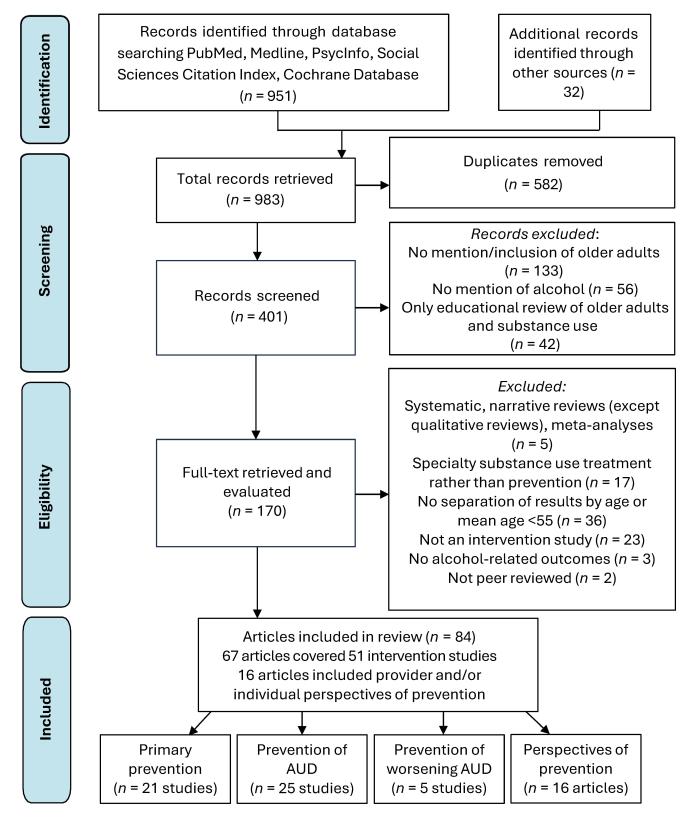

The literature search was conducted in December 2024 according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines of systematic reviews (see Figure 1).37 Searches occurred across multiple databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, World of Science, Cochrane Database, Social Sciences Citation Index, and PsycInfo. Boolean search terms—including “alcohol*,” “drinking,” “alcohol use,” or “alcohol outcomes”; “older adults,” “elderly,” or “seniors”; “intervention” or “brief intervention,” “prevention,” and “SBIRT”—were used in different combinations. Ancestry methods identified additional studies from study reference sections absent from the above-described searches. Studies were required to be peer-reviewed and published, although this requirement excluded major older adult prevention initiatives. A total of 983 records published from 1999 to 2024 were identified. After removing duplicates, 401 abstracts were screened for a focus on: (1) older adults or an adult population that typically includes substantial numbers of adults ages 50 and older (e.g., veterans); (2) alcohol use or a related outcome; and (3) a psychosocial intervention. Full texts were retrieved for 170 records.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of review procedures. Source: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Studies were included in the review if they: (1) had a mean age of 55 and older or a labeled subsample of individuals age 50 and older; (2) reported intervention outcomes or described the perspectives of older adults and/or providers on prevention interventions. Full texts were excluded if they: (1) were quantitative systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or reviews of reviews (qualitative systematic reviews were retained); (2) were not peer-reviewed; (3) covered pharmacological interventions; (4) described interventions set in a formal, specialty substance use treatment program; or (5) excluded alcohol outcomes. One study was excluded because its reported results conflicted with its conclusions.38 This resulted in 84 records (comprising 51 studies) on outcomes of alcohol prevention interventions and an additional 16 articles on participant and provider prevention intervention experiences.

Data extraction included sample description (size, mean/median age; race/ethnicity, and sex); years of data collection to identify generational cohorts; study design, setting, and intervention modality/approach; description of the intervention and its comparator; primary outcomes assessed; and findings. Outcomes of alcohol use (i.e., reported quantity and/or frequency of drinking) and alcohol-related targets (i.e., risk level, consequences of alcohol use, completed screenings, planning for change) were specific to each study. Intervention studies were sorted into three categories, relating to public health definitions of primary (i.e., disease prevention), secondary (i.e., early disease detection and intervention) and tertiary prevention (i.e., reduction in disease severity).39 This included primary prevention studies (n = 21), secondary prevention studies of AUD (n = 25), and tertiary prevention of worsening AUD severity (n = 5). Within each prevention category, results were organized by study design (i.e., pre-to-post, comparison designs [randomized or quasi-comparison], and RCTs) as a proxy for study bias and rigor. Prevention intervention barriers and facilitators were identified from all 84 articles and synthesized.

Results

Overall Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the 51 intervention studies. These studies collected data from 1993 to 2021 and included participants from four generations: GG (included in 31% of studies), TSG (96% of studies), BB (57% of studies), and Gen X (14% of studies). None of the studies had a sample consisting predominantly (greater than 68%) or exclusively of GG participants. Among RCTs, TSG was the predominant generation in 75% of studies; BB participants were included with other generations in 25% of studies and were the predominant generation in 12% of studies. No study included a predominance of Gen X participants.

| Characteristics | Primary Prevention Studies (n = 21) n (%) |

Secondary Prevention Studies (n = 25) n (%) |

Tertiary Prevention Studies (n = 5) n (%) |

Total Studies (N = 51) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||

| United States | 16 (76.2) | 17 (68.0) | 4 (80.0) | 37 (72.5) |

| United Kingdom | 3 (14.3) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 6 (11.8) |

| Australia | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| Denmark | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| China | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Croatia | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Spain | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Sweden | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Demographics | ||||

| Generations included | ||||

| GG/TSG | 5 (23.8) | 9 (36.0) | 1 (20.0) | 15 (29.4) |

| GG/TSG/BB | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| TSG only | 2 (9.5) | 6 (24.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (15.7) |

| TSG/BB | 11 (52.4) | 7 (28.0) | 2 (40.0) | 20 (39.2) |

| TSG/BB/Gen X | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (9.8) |

| BB only | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| BB/Gen X | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| 24% or more non-White | 5 (23.8) | 8 (32.0) | 2 (40.0) | 15 (29.4) |

| 50% or more female | 14 (66.7) | 7 (28.0) | 3 (60.0) | 24 (47.1) |

| Study Design | ||||

| Pre-to-posttest | 12 (57.1) | 4 (16.0) | 0 (0) | 16 (31.4) |

| Randomized comparison trial or quasi comparison design | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (40.0) | 4 (7.8) |

| Randomized controlled trial | 8 (38.1) | 20 (80.0) | 3 (60.0) | 31 (60.8) |

| Setting (not mutually exclusive) | ||||

| Primary care | 9 (42.9) | 14 (56.0) | 1 (20.0) | 24 (47.1) |

| Specialty clinic for disease/injury | 1 (4.8) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.9) |

| Hospital/emergency department/in-patient setting | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (9.8) |

| Community, senior centers | 6 (28.6) | 4 (16.0) | 1 (20.0) | 11 (21.6) |

| Outpatient research setting | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (5.9) |

| Website/online | 3 (14.3) | 5 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (15.7) |

| Pharmacy | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Modality (not mutually exclusive) | ||||

| 1 (4.8) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Booklet, pamphlet, report | 3 (14.3) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (9.8) |

| In person (group or one-on-one) | 11 (52.4) | 18 (72.0) | 5 (100) | 34 (66.7) |

| Online, video conference | 5 (23.8) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (15.7) |

| Telephone | 1 (4.8) | 6 (24.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (13.7) |

| Computer in office | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| Mobile or smartphone | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.9) |

| Design/Adaptation | ||||

| Older-adult specific | 15 (71.4) | 16 (64.0) | 2 (40.0) | 33 (64.7) |

| Approach (not mutually exclusive) | ||||

| Psychoeducation | 10 (47.6) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 13 (25.5) |

| Motivational interviewing | 2 (9.5) | 11 (44.0) | 5 (100) | 18 (35.3) |

| Brief alcohol intervention/SBIRT | 5 (23.8) | 8 (32.0) | 2 (40.0) | 15 (29.4) |

| Brief advice | 1 (4.8) | 7 (28.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (15.7) |

| Brief negotiated interview | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (5.7) |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (40.0) | 5 (9.8) |

| Goal setting | 1 (4.8) | 2 (8.0) | 2 (40.0) | 5 (9.8) |

| Normative or personalized feedback | 0 (0) | 5 (20.0) | 3 (60.0) | 12 (23.5) |

| Text messaging | 4 (19.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| Daily self-monitoring | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.9) |

| Review of workbook | 4 (19.0) | 8 (32.0) | 0 (0) | 12 (23.5) |

| Physician involvement | 3 (14.3) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 6 (11.8) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (60.0) | 7 (13.7) |

| Intervention Characteristics | ||||

| Only one contact | 20 (95.2) | 6 (24.0) | 0 (0) | 26 (51.0) |

| Multiple contacts | 1 (4.8) | 19 (76.0) | 5 (100) | 25 (49.0) |

| Contact time less than 1 hour | 5 (23.8) | 7 (28.0) | 0 (0) | 12 (23.5) |

| Contact time 1 hour or more | 3 (13.6) | 11 (44.4) | 5 (100) | 19 (37.3) |

| Time not reported | 12 (61.9) | 8 (28.0) | 0 (0) | 20 (39.2) |

| Not possible to track (mail, text) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| Types of Outcomes (not mutually exclusive) | ||||

| Knowledge only | 6 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (11.8) |

| Intention/plan to change only | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.8) |

| Completed screen | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.9) |

| Treatment engagement or completion | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (3.9) |

| Alcohol use (quantity/frequency) | 10 (47.6) | 25 (100) | 3 (60.0) | 38 (74.5) |

| Reduced harm (i.e., at-risk drinking) | 12 (57.1) | 25 (100) | 3 (60.0) | 40 (78.4) |

| Discharge to home | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Intervention Achieved Target Goal | ||||

| Knowledge only | 6/6 (100)* | 0/0 (0)* | 0/0 (0)* | 6/6 (100)* |

| Intention/plan to change only | 4/4 (100)* | 0/0 (0)* | 0/0 (0)* | 4/4 (100)* |

| Completed screen | 2/2 (100)* | 0/0 (0)* | 0/0 (0)* | 2/2 (100)* |

| Treatment engagement or completion | 0/0 (0)* | 1/1 (100)* | 1/1 (100)* | 2/2 (100)* |

| Reduced quantity/frequency of alcohol | 4/10 (40.0)* | 13/25 (52.0)* | 3/3 (100)* | 20/38 (65.8)* |

| Statistically significant proportion reduced at-risk drinking | 7/12 (58.3)* | 23/25 (92.0)* | 2/2 (100)* | 32/39 (87.1)* |

| Discharge to home from skilled nursing facility | 0/0 (0)* | 0/0 (0)* | 1/1 (100)* | 1/1 (100)* |

*Percentages are by row, rather than column.

Note: More than one option could apply to a study, so values do not necessarily add up to 100%. BB, Baby Boomers; Gen X, Generation X; GG, Greatest Generation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SBIRT, Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment; TSG, The Silent Generation.

Most studies had samples with primarily White participants, with a third including more than 24% non-White participants. Almost half (47%) had samples with a majority of females, although males historically drink more and therefore would be expected to be more likely to participate. The most common intervention setting was primary care (45%), with a fifth delivered in a community agency and another fifth online. Prevention interventions were largely provided in person, some with a follow-up telephone or mail component. Some interventions were completely delivered remotely by mail, online, a smartphone app, or text messaging. Two-thirds of the interventions were adapted specifically for older adults. Interventions used mostly “motivational approaches” (77%), such as motivational interviewing,40 motivational enhancement therapy,41 SBIRT,42 and/or a feedback, responsibility, advice, menu of options, empathy, and self-efficacy (FRAMES) approach.43 Only three studies measured intervention fidelity.44-46 A quarter of the studies provided psychoeducation, and one-fifth used normative and/or personalized feedback. Among the 61% of studies that reported the number and duration of contacts with participants, about half occurred in one contact, ranging from 5 to 60 minutes, and half had multiple contacts (ranging from a total of 1 hour to 16 or more hours).

Focal outcomes were alcohol-related (e.g., completed screens; treatment engagement; reducing alcohol-related problems, harm, or risk level for consequences) and/or alcohol consumption (i.e., quantity, frequency of drinking, proportion of at-risk drinking). For alcohol-related outcomes, all prevention interventions successfully impacted their target outcome at intervention end. For alcohol consumption, the findings were mixed. Half of the interventions reduced the quantity and/or frequency of alcohol use (measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption [AUDIT-C]47 or Timeline Followback).48 Additionally, 79% of interventions reduced harm, such as alcohol-related consequences or behaviors as measured by the AUDIT,49 the Alcohol-Related Problems Survey (ARPS),50 its descendant the Comorbidity-Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool (CARET),51 and the Alcohol, Smoking, Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST).52 Notably, many RCTs reported significantly reduced alcohol use across conditions, including control conditions or active comparators, potentially indicating that assessment itself had a therapeutic effect among older adults.

Primary Prevention Interventions

Pre-to-posttest designs

Of the 12 primary prevention interventions evaluated using pre-to-posttest designs (see Appendix 1), 11 resulted in significant increases in knowledge, completed screening, intention to change or talk to a professional, and decreases in alcohol use and risk level, where measured. Studies were mostly set in primary care offices and senior centers, with interventions ranging from simple brochures to class-like formats; sample sizes ranged from 26 to just under 18,000 participants. Studies are organized by their target outcome below.

Increased knowledge as outcome

All five studies aimed at increasing knowledge of alcohol-related risks reported significant increases in knowledge immediately after the intervention.53,54,56,57,59 Three of the studies53,56,57 provided in-person group education in a senior center, with two53,57 (one with GG/TSG participants, one with TSG/BB participants) utilizing a class-like format. Only one of these two studies demonstrated sustained knowledge at 6 months, with slippage in some areas.57 A third study implemented an intervention called Prevention BINGO with 348 TSG/BB participants.56 Gameboard squares were facts about alcohol use and relevant risks, and participants earned prizes. Participants’ increased knowledge was sustained 1 month later. Two other studies54,59 offered effective one-on-one education—one delivered it via a 36-page booklet or pamphlet to GG/TSG participants in a primary care waiting room,54 the other via a short video public service announcement, a poster, and a brochure to TSG/BB participants at a pharmacy.59,62 In the primary care setting, participants preferred the booklet over the pamphlet;54 in the pharmacy setting, participants preferred all three mediums together.59

Intention to talk with a professional about drinking as outcome

Two studies tested participants’ immediate intention to discuss alcohol use with a professional after reviewing educational materials.55,59 Among GG/TSG older adults who completed the ARPS78 and received older adult-specific feedback in a primary care waiting room, 31% intended to talk to their primary care physician about their alcohol use.55 A second study in a pharmacy with TSG/BB older adults increased knowledge, but participants reported no intention of discussing drinking with a pharmacist.59

Completed screening as outcome

One study demonstrated a threefold increase in alcohol screening among TSG/BB older adults when screening was included in an online Medicare annual wellness visit.67

Plan for change as outcome

Four studies20,57,58,62,63 used plan for change post-intervention as a proxy outcome. The online service Alcoholscreening.org assesses visitors’ alcohol consumption through a brief assessment and provides both normative feedback (comparison to peers’ drinking) and personalized feedback (risk-related feedback).58 In 2013, TSG/BB visitors (n = ~17,600) to the site had significantly (~50%) higher odds of initiating a plan for change compared to those under age 50. In another study comparing types of online-delivered older adult-specific feedback (normative vs. personalized feedback) with BB/Gen X older adults, 44% of participants across conditions planned to reduce drinking.63 A subsequent analysis showed that older men receiving normative feedback were more likely to plan for change.79 Another study implemented a 5-minute, in-person brief intervention in atypical settings (e.g., grocery stores) with TSG/BB/Gen X older adults; 40% of older adults drinking beyond low-risk guidelines intended to change.20 Finally, the previously mentioned pharmacy-based study with TSG/BB older adults that implemented multipronged psychoeducation did not increase intention to change drinking.59

Reduced at-risk drinking as outcome

Two studies65,66 tested SBIRT delivered by nonphysicians with TSG/BB older adults, both of which included a relatively high proportion of non-White participants. One study sample had 12% participants age 65 and older and 37% non-White participants.66 At 6 months, those age 65 and older had the lowest intervention response of any age group, showing an 11% reduction in at-risk drinking compared to 20% among younger adults. The other study sample included only adults age 60 and older, of whom 95% were African American.65 The intervention was tailored to older adults, and findings demonstrated a 65% reduction in at-risk drinking at 6 months.65 The study’s intentional use of participants’ long-established relationships with health care providers may be a reason for its success. A third study—the pharmacy-based psychoeducation with TSG/BB described above that did not increase intention to change—found that individuals in the sample who consumed alcohol beyond low-risk levels cut their drinking from 15 drinks per week to seven drinks per week 3 months later.62

Randomized comparison study

One study compared the effectiveness of two online interventions using increases in completed screening and access to further resources as outcomes.68 To increase online screening engagement, visitors to the drinkaware.co.uk website randomly received health- or appearance-based alcohol banner messages to determine which led to greater AUDIT-C47 screening completion. Banner messages appeared at the top of a computer or mobile phone screen, displaying either a message about how drinking affects one’s health or how drinking affects one’s appearance, such as premature aging.68 Among adults ages 45 to 64 (mostly BBs ages 50 to 68 and Gen X ages 45 to 49), both health- and appearance-based messages led to screening and accessing resources; however, for adults age 65 and older (mostly TSG), appearance-based messages led to significantly more completed screens.

Randomized controlled trials

Alcohol use and at-risk drinking as outcomes

Among seven RCTs testing primary prevention interventions for alcohol use that reported drinking outcomes,70-77 only one demonstrated a significant effect compared to usual care.70 Fink et al.70 implemented a primary care prevention intervention with GG/TSG older adults. After completing the older adult-specific ARPS,80 participants were randomized to one of three arms: (1) usual care; (2) a feedback and education report given to the participant; or (3) a report given to both the participant and the primary care physician (combined report). At 12 months, older adults in the patient-only report group were 59% more likely to drink at low-risk levels according to the ARPS compared with those who received usual care. With the combined report, participants were 23% more likely to drink at low-risk levels compared with those receiving usual care. However, it was only the combined report that demonstrated a significant, though small, reduction in standard drinks (just over one standard drink) at follow-up compared to usual care—the only significant finding in terms of alcohol consumption. In contrast, the same investigators later tested the effectiveness of an educational website to teach older adults to balance risks and benefits of alcohol use among TSG/BB older adults outside primary care compared to no intervention;76 both groups reduced drinking by about two drinks per week.

Treatment engagement as outcome

The Healthy Profiles Study69 compared a brief alcohol intervention booklet to a general health advice booklet provided within primary care among TSG male veterans. Alcohol use outcomes could not be ascertained, but the alcohol booklet increased participants’ use of outpatient specialty care compared to the general health booklet at 9 months. No other differences were reported.

Healthy lifestyles as outcome

Five RCTs of interventions that aimed to improve healthy lifestyles among GG/TSG older adults or recruited TSG/BB older adults coping with health problems or events (e.g., hospitalization, emergency department visit, bone density scan, stroke patients) found that the interventions were not effective in significantly reducing alcohol use.71-73,75,77 Intervention modalities varied across studies (four were delivered in person, three involved printed materials, one was delivered online). Two RCTs addressing overall lifestyle among GG/TSG older adults71,72 intervened with the participants or their primary care physician separately. Neither approach reduced alcohol use at the 1-year follow-up.

Summary of findings from primary prevention studies

Existing primary prevention interventions among older adults increased knowledge about alcohol use and its potential harms in later life in pre-to-posttests,53,54,56,57,59,62 increased both initiation and completion of screens for alcohol use,67,68 prompted intention to talk to a physician68 (but not a pharmacist59) about drinking, and prompted planning or intention to change.20,58,63 Within-group studies of TSG/BB older adults revealed that SBIRT delivered by a nonphysician yielded a lower response among those age 65 and older compared to younger adults; however, a tailored, older adult-specific SBIRT intervention in primary care settings and senior centers significantly reduced alcohol use across time, with AUDIT-C measured risk identified in fewer and fewer cases across time.65 Only 1 out of 7 primary prevention RCTs demonstrated significant decreases in at-risk drinking compared to the control condition,70 an effect that was strongest when only participants and not their physicians received the report on the alcohol assessment. This RCT took place from 2000 to 2003 among GG/TSG older adults. Since then, no other RCT has demonstrated this same effect for a primary prevention intervention. RCTs that found no significant effects were focused on overall lifestyles, multiple target behaviors, or implemented among individuals experiencing severe health issues. Participants in acute care may have been too ill or compromised to respond to the interventions,75,77 and passive feedback73 may have been ignored altogether. A few studies focused on engaging older adults in screening or education, which led to innovations such as gamification56 and alternative messaging.68

Secondary Prevention Interventions for AUD and Alcohol-Related Problems

Of 25 secondary prevention interventions for AUD assessed (see Appendix 2), four were assessed using pre-to-posttest designs,22,23,81-83 one with a randomized comparison trial,84 and 20 with RCTs.44,85-91,93-97,99,100,102-113 Studies focused on mostly male GG/TSG older adults, implementing interventions using multiple, longer contacts, and 62% were older adult-specific. A majority were set in primary care (56%), followed by online (20%).

Pre-to-posttest designs

All four pre-to-posttest studies22,23,81-83 reported significant reductions in alcohol use after the intervention among older adults with at-risk drinking (see Appendix 2). Three interventions were delivered in person;22,23,81,82 the fourth was online.83 U.S.-based study samples had about 20% non-White participants. Studies are summarized in chronological order below.

The Florida Brief Intervention and Treatment for Elders (BRITE) Project22,23 was implemented in two phases—a pilot phase and a larger SBIRT initiative—implemented from 2004 to 2011. Across both phases, 88,498 GG/TSG/BB older adults were screened in community settings and participants’ homes by health educators, with 11,663 individuals screening positive for substance misuse. Screening assessed alcohol use (pilot: AUDIT49 and Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test-Geriatric Version [SMAST-G];114 larger study; ASSIST52), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2115,116 and Geriatric Depression Scale, Short Form117), and/or anxiety (pilot: taking anti-anxiety medication23). Participants screening positive for alcohol misuse were offered SBIRT, with the option of up to five 1-hour sessions in Phase 1 or up to 16 or more sessions in Phase 2, including motivational interviewing and, if needed, older adult-specific cognitive behavioral therapy modules.10 Health educators determined the number of sessions needed for an individual, with most ending without implementing cognitive behavioral therapy.10 In Phase 1, only 19% of the 169 GG/TSG participants with at-risk drinking at baseline remained positive for at-risk drinking 30 days post-discharge.23 In Phase 2, TSG/BB participants with 6-month data reported a reduction in any alcohol use (45% of participants), having five or more drinks in one sitting (23% of participants), and drinking to intoxication (10% of participants).22 Results should be interpreted cautiously given that out of the 6,600 participants who received services only 171 completed follow-up.

The Older Wiser Lifestyles intervention81,82 adapted the ARPS for Australian TSG older adults age 60 and older who drank alcohol in the past month. Those who screened positive for at-risk drinking were invited to a primary care clinic for an in-person, stepped-care intervention. Older adults with low-risk drinking were provided minimal education. Older adults with at-risk drinking were assessed for readiness to change, and brief interventions were tailored accordingly. Those in the precontemplation stage received a 1-hour session of psychoeducation; those in the contemplation stage received up to 5 hours of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. Over half (54%) of those at-risk drinking received just one session, with participants reporting it was sufficient.81,82 AUDIT-C scores were significantly reduced at the 6-month follow-up, yet 36% of participants continued at-risk drinking.

Lastly, a smartphone app adapted a cognitive approach bias modification intervention for BB/Gen X Australians.83 Older adults who drank beyond low-risk guidelines trained on the app twice per week for 4 weeks using their personal smartphone. At-risk drinking decreased for both for single sittings (down 16%) and total weekly consumption (down 22%) after the intervention, with a mean reduction of consumption of 5.4 drinks per week.

Randomized comparison study

Sedotto et al.84 randomly assigned adults to one of two digital, non–age-specific interventions: Step Away, an eight-module, smartphone app-based intervention and a Facebook chatbot (see Appendix 2). The app required participant initiation, whereas the chatbot was less formal and initiated daily check-ins. Significant alcohol use reduction occurred across conditions and age groups; overall, there was a reduction in consumption of about 1 drink per drinking day and a 28% increase in days abstinent. However, BB/Gen X older adults engaged twice as often as younger adults across the interventions to achieve this reduction. Older adults may need greater digital intervention exposure for equivalent therapeutic effect.

Secondary prevention interventions tested with RCTs

RCTs addressed at-risk drinking among only older adults (n = 18) or compared them to younger adults (n = 2) (see Appendix 2). Fifteen interventions were older-adult specific.85,86,88-91,93-97,99,100,102,104-110,113 Fourteen studies were conducted in primary care;85-88,90,91,93-97,99,100,102,104-107,109,110,113 additional settings included community agencies, inpatient and outpatient hospital units, and online. Sixteen RCTs were at least partly in-person;44,81,82,87,89,93-97,99-101,104-107,109,110,112 five had follow-up telephone calls.44,89,96,97,99-101 Primary outcomes were alcohol use, proportion of people with at-risk drinking, treatment engagement, and health care utilization. Six RCTs reported significant effects in favor of prevention intervention compared to controls.85,88,96,99,108,111 Seven studies had mixed findings, with significant results in favor of the prevention intervention only for a sample subgroup.90,91,93-95,103,110,118 Eight RCTs found no effect across conditions.44,87,89,91,104,106,107,109,112

RCTs with significant positive effects

Project Guiding Older Adult Lifestyles85 tested a primary care-based alcohol prevention intervention tailored to GG/TSG compared to usual care. The intervention consisted of two 10- to 15-minute counseling sessions (1 month apart) with a primary care physician, during which participants received brief advice and psychoeducation on drinking risks, reviewed an information booklet, and contracted for change. Weekly alcohol use declined by 36% and binge drinking by 47% in the intervention group compared to control at 12 months,85 and this decline was sustained 24 months later.86 Generalizability of findings was limited because only 35% of participants were female and other demographics were not reported.

Another study randomized mostly male, non-White TSG veterans with depression and/or at-risk drinking to usual care or telephone disease management plus usual care.88 Telephone disease management included six calls with a behavioral health specialist nurse, during which participants completed an older adult-specific workbook to reduce drinking, for a total of 4.5 hours over 24 weeks. Follow-up occurred at 4 months, before intervention end. Telephone disease management plus usual care was superior to usual care alone in treatment engagement (43.8% vs. 20%, respectively), reduction in drinks per week (9 units vs. 2 units, respectively), and reduction in binge episodes over a 3-month period (26 episodes vs. 1 episode, respectively).88

The Healthy Living as You Age study96,97 focused on TSG/BB older adults with at-risk drinking; the sample included 22% Hispanic or non-White individuals, and 29% were female. All participants were screened using the CARET,51 an ARPS descendent, and then randomized to receive a general health booklet or a prevention intervention. The intervention consisted of a daily diary of alcohol use before a primary care visit, primary care brief advice using an older adult-specific booklet, and three sessions of motivational interviewing with a health educator, totaling 80 minutes. At-risk drinking was significantly reduced at 3 months in the intervention group compared to controls.96,97 Although a reduction was sustained at 12 months, only past-week drinking remained significantly different from control.96 Older adults who received all three health educator calls had more than five times greater odds of not exhibiting at-risk drinking compared with those who received no calls at 3 months but not 12 months.97

Project Share99,100,102 randomized TSG older adults to usual care or an intervention that included mailed psychoeducation booklets/tip sheets, a daily diary of drinking before a primary care visit, a discussion with a primary care physician, and three health educator calls, totaling 27 minutes. Primary care physicians were asked to discuss alcohol use at each visit for a year. If a physician discussion occurred, odds of at-risk drinking at 12 months decreased by 39%, and if both a daily diary and agreement to reduce drinking were completed, odds decreased by 55%.100

Two prevention interventions, one mail-based108 and the other text messaging-based,111 demonstrated significant effects among older adults. TSG/BB older adults from a primary care network identified as exhibiting at-risk drinking were randomized to receive either mailed brief personalized feedback (based on the CARET) with booklets on alcohol and aging119 or assessment only.108 At 3 months, the intervention group significantly reduced at-risk drinking by 22%, alcohol medication co-use by 15%, and symptoms of medical or psychiatric conditions by 20% compared to the control group. Using secondary analysis, another study examined pilot RCT data comparing 12 weeks of non-age-specific daily text messaging to assessment only to reduce at-risk drinking.111,120 BB adults age 50 and older were compared to younger adults. Text messaging reduced drinking by about 5 units per week and 1 unit per day across age groups by 3 months compared to assessment only. Younger adults had slightly larger effects than older adults. Older adults had a stronger response to gain-framed messages (e.g., messages about the benefits of reducing alcohol use), whereas younger adults responded more to loss-framed messages (e.g., messages about the negative consequences of drinking).

RCTs with mixed findings on alcohol use

Five studies90,91,93-95,118 were part of the Primary Care Research in Substance Abuse and Mental Health for the Elderly (PRISM-E) project. PRISM-E compared “integrated care,” defined as combined mental health and substance use treatment in primary care, to “enhanced referral to specialty care” on engagement with specialty treatment and alcohol use. Ten sites across the United States enrolled more than 2,000 TSG older adults,90 with 26% female and 48% non-White participants. Each site followed set guidelines for the conditions yet tailored protocol details to fit their site’s needs.118 In integrated care, all sites provided a brief intervention with an age-specific workbook. Some sites offered additional sessions after the brief intervention or comprehensive geriatric care of differing intensity and professional make-up.95 Treatment engagement was higher with integrated care (71% of participants) compared with enhanced treatment referral (49%); however, given intervention variability, determining the components responsible for this difference is complex.90 An analysis of three sites found no significant condition differences for alcohol use at 6 months; however, the authors noted that although 43% of participants in the integrated care group received at least one session of the brief intervention, only 9% received all three sessions offered at this particular site.91 A single site (n = 34), which emphasized harm reduction via three sessions of motivational interviewing within integrated care, reported that those assigned to integrated care were significantly more likely to access specialty care and reduce drinking compared to enhanced referral.94 Another analysis of 12-month data from male veterans with at-risk drinking within the PRISM-E project found reduced binge drinking.93 One site treating veterans implemented integrated care with an interdisciplinary team of geriatric specialists; this approach demonstrated a 75% reduction in the likelihood of at-risk drinking compared to enhanced referral.95 Overall, setting attributes, drinking severity, and intervention exposure contributed to distinct outcomes across sites. Thus, sites with more completed sessions and/or services91,93,94 within integrated care appeared to be associated with increased treatment engagement and reduced at-risk drinking compared to enhanced referral; notably, enhanced referral also performed well at these sites.

Some studies noted differences in response to the interventions by sex. A Danish RCT tested an online intervention among 1,380 TSG/BB older adults.103 Participants were randomized to one of three arms: personalized and normative feedback, brief advice, or a control. All groups reduced drinking by about 6 units per week at 12 months; however, males were found to respond significantly more to personalized and normative feedback than to the other two conditions.

A Spanish RCT evaluated in-person brief interventions in health centers and homes at four time points over 12 months compared to brief advice given at the first visit.110 Significant intervention effects were found only among women, who were four times as likely to have reduced drinking compared to controls.

RCTs with null findings

Five studies in primary care settings found no effects of the interventions.44,87,104,106,109 Three of the studies44,104,109 reported methodological issues, namely poor compliance, poor competence in intervention delivery, or low exposure to the intervention; however, two methodologically strong studies87,106 also found no condition differences. Cucciare et al.106 randomized mostly male TSG/BB veterans who screened positive for at-risk drinking to either web-based normative feedback (with brief advice) or usual care. At 12 months, both groups reduced heavy drinking days by 50%, reduced consumption by one drink per day, and had three fewer drinking days per month. Gordon et al.87 compared the efficacy of motivational enhancement treatment, brief advice, or usual care among adults drinking beyond low-risk guidelines. All groups, regardless of condition or age, significantly reduced drinking at 12 months, yet GG/TSG older adults age 65 and older still drank beyond low-risk guidelines.

Outside of primary care, two studies implemented prevention interventions with injured TSG/BB/Gen X older adults112 or ill GG/TSG patients89 in a hospital setting compared to usual care. Both studies had null findings, similar to primary prevention studies that targeted ill or injured older adults.89,112

Summary of findings from secondary prevention studies

Pre-to-posttests of secondary prevention interventions22,23,81-83 included multiple contacts with participating older adults and demonstrated significant reductions in at-risk drinking, averaging a reduction in alcohol use by about half across studies. Secondary prevention interventions tested with RCTs that demonstrated a significant therapeutic effect compared to the control or comparison group shared important features. All six of these studies85,88,96,99,108,111 focused on one outcome—reduced at-risk drinking—and all were focused on TSG individuals, with one study including GG older adults.85 Five of the six studies85,88,96,99,111 had interventions with clearly defined multiple points of contact, and four had a behavioral nurse specialist or physician involved.85,88,96,99 Three digital interventions,84,111 focused on TSG/BB and BB/Gen X individuals, significantly reduced drinking among younger and older adults. Older adults engaged more with interactive digital interventions84 and responded differentially to distinct text messaging types compared to younger adults.111 All three digital interventions had multiple points of contact, and no professional was involved. Secondary prevention interventions that yielded null findings were largely methodologically flawed,44,104,109 appeared to have limited treatment exposure, 91 or had only a single point of intervention contact.87

Tertiary Prevention of Worsening AUD Outside of Formal Treatment

Five studies involved individuals with AUD outside specialty treatment. Two were quasi-comparison studies,46,121,122 two were randomized comparison trials,123-125 and one was an RCT45 (see Appendix 3). All tertiary prevention interventions were delivered in person, with mostly TSG/BB individuals, and had significant therapeutic effects. Two interventions were specifically designed for older adults.121,123,126 Four used motivational interviewing and/or cognitive behavioral therapy.45,46,123-125

Quasi-comparison studies

Both tertiary prevention interventions that were tested using comparison with no treatment without randomization reduced alcohol use.46,121 A single-system analysis examined 38 GG/TSG/BB individuals (age 54 and older) from three RCTs testing non-age-specific brief treatments for AUD.46 Older adults in active treatments reduced drinking twice as often as those receiving no treatment by the end of the treatment period. A second study aimed to increase discharges to home among older adults with substance use histories in a skilled nursing facility. The facility offered an onsite recovery program,121,126 including general/specialty counseling, family therapy, and 12-step meetings, with supportive home visits after discharge. Odds of discharge to home of individuals participating in the recovery program were three times those of individuals who did not participate in the program.

Randomized comparison and controlled trials

Three studies each aimed to test the impact of two active treatments.45,123-125 A Swedish study randomized TSG/BB/Gen X older adults to two active brief treatments pathways—the “15-method” or specialty alcohol treatment. Both conditions provided brief advice with a physician and pharmacological and/or psychosocial treatment for AUD.124,125 Neither treatment was specific to older adults, and the “15-method” was briefer than specialty care. At 12 months, alcohol use was reduced across groups, with no moderating effect of age, and participants preferred specialty care.124,125 Another study randomized TSG older adults either to a community-based/in-home prevention intervention providing geriatric care management, or to direct referral to enhance specialty treatment completion.123 The geriatric care management included motivational interviewing and multiple points of contact. Compared to direct referral to specialty care, the intervention group had approximately 30% higher rates of inpatient and outpatient treatment completion. Finally, data from two RCTs were combined to explore the effectiveness of four sessions of motivational interviewing versus four sessions of nondirective listening for 8 weeks across age groups.45 Older adults age 51 and older responded best to the high-quality motivational interviewing; however, this approach reduced drinking only 8% more than did nondirective listening by week eight.

Summary of findings from tertiary prevention studies

Tertiary prevention studies that offered more points of contact and services appear to be the most preferred, significantly reduced alcohol use, or increased treatment completion. When compared to no treatment,46,121,122 active interventions that included pharmacology and counseling demonstrated greater drink reduction. When active interventions were compared to one another,45,127 drinking outcomes were equivalent or demonstrated minimal difference.

Intersection of Age, Period, and Generation

Table 2 lists the interventions that demonstrated at least preliminary effectiveness compared to another existing treatment or to control in the context of an RCT, organized by decade of age of participants, years of data collection, and the predominant generation included in the sample. Of 14 RCTs with positive findings (see Table 2),45,69,70,85,88,90,93-96,99,108,111,123 across decades of age, only three45,108,111 collected data before 2008. Those three completed data collection in or before 2016.

| Ages by Decade | Study* | Years Data Collected | Predominant Generation Represented† | Type of Prevention Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50-60 | Copeland et al. (2003)69 | 1994-1999 | TSG | Primary |

| Oslin et al. (2003)88 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Kuerbis et al. (2023)45 | 2008-2009, 2012-2016 | BB | Tertiary | |

| Kuerbis et al. (2015)108 | 2011-2012 | BB | Secondary | |

| Kuerbis et al. (2022)111 | 2014-2015 | BB | Secondary | |

| 61-70 | Fleming et al. (1999)85 | 1993-1995 | TSG | Primary |

| Copeland et al. (2003)69 | 1994-1999 | TSG | Primary | |

| Oslin et al. (2003)88 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Primary | |

| Bartels et al. (2004)90 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Zanjani et al. (2008)93 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Wooten et al. (2017)95 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Lee et al. (2009)94 | 2001-2005 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Moore et al. (2011)96 | 2004-2007 | TSG | Secondary | |

| D’Agostino et al. (2006)123 | NR‡ | TSG | Tertiary | |

| Ettner et al. (2014)99 | 2005-2007 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Kuerbis et al. (2023)45 | 2008-2009, 2012-2016 | TSG/BB | Tertiary | |

| Kuerbis et al. (2015)108 | 2011-2012 | TSG/BB | Secondary | |

| 71-80 | Fleming et al. (1999)85 | 1993-1995 | GG | Primary |

| Bartels et al. (2004)90 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Zanjani et al. (2008)93 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Lee et al. (2009)94 | 2001-2005 | GG/TSG | Secondary | |

| Wooten et al. (2017)95 | 2000-2001 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Fink et al. (2005)70 | 2000-2003 | GG/TSG | Primary | |

| Moore et al. (2011)96 | 2004-2007 | TSG | Secondary | |

| Ettner et al. (2014)99 | 2005-2007 | TSG | Secondary | |

| D’Agostino et al. (2006)123 | NR‡ | TSG | Tertiary |

*Some studies fell into more than one age decade.

† Defined as the generation that covered the widest span of participants according to age (mean +/− 1 SD) and years of data collection.

‡ Used date of publication and year before.

Note: BB, Baby Boomers; GG, Greatest Generation; TSG, The Silent Generation.

Among older adults ages 50 to 60, five RCTs45,69,88,108,111 with favorable results for the intervention were implemented with TSG or BB individuals. Two studies108,111 outside of primary care found preliminary intervention effectiveness among BBs ages 50 to 60 for secondary prevention only. In contrast, nine RCTs44,76,77,103,104,106,107,109,112,124,125 had null or equivalent findings among predominantly BBs ages 50 to 60.

Among older adults ages 61 to 70, 12 RCTs45,69,85,88,90,93-96,99,108,111,123 noted significant differences, including 10 with TSG individuals69,85,88,90,93-96,99,123 and two with TSG/BB individuals.45,108 Two primary prevention interventions85,88 and seven secondary prevention interventions69,90,93-96,99 with TSG older adults were set in or connected to medical settings and contained multiple points of contact. Two tertiary prevention studies with participants in this age group found a significant effect.45,123 One offered multiple services in the context of geriatric case management with TSG individuals,123 and the other found a small effect for motivational interviewing among BB individuals over nondirective listening.45 In contrast, six studies75,87,89,91,104,110 of predominantly TSG individuals and two with a combination of TSG/BB individuals73,109 in this age group found no significant effects, thought to be due to methodological issues and/or minimal intervention. One methodological exception among the null studies was a U.K. study set in primary care that provided stepped care for alcohol use compared to 5 minutes of brief advice with a nurse for TSG/BB individuals.104 Six studies with predominantly BB individuals found no significant effects.44,77,103,106,107,112,124,125

Among older adults ages 71 to 80, two primary prevention interventions took place in primary care, one with GG85 and one with GG/TSG individuals.70 Six secondary prevention interventions,90,93-96,99 four of which were part of PRISM-E,90,93-95 and one tertiary prevention intervention served TSG individuals.123 In contrast, seven studies71,72,75,87,89,91,110 with TSG individuals with null findings included ill or injured participants, minimal interventions, and/or had multiple target behaviors. No study included BB participants in their 70s.

Barriers and Facilitators of Successful Prevention Interventions

The studies reviewed here identified numerous barriers to successful older adult prevention interventions (see the box “Potential Barriers to Successful Prevention Interventions Among Older Adults”). Organizational level barriers included limited resources, payment structures that discourage SBIRT, and lack of leadership commitment to prevention intervention sustainment beyond study end.60,65,66,128,129 In acute health care settings, prevention interventions failed to impact alcohol use because other health concerns may be more pressing.75,77 Further, interventions that target too many behaviors at once,67,71,72 are too passive (e.g., a letter),73 or have unverified or low exposure to intervention dose,26,91,97,104,128 were ineffective in producing alcohol-related behavior change. Qualitative studies found that providers who did not believe older adults drink alcohol and/or could change, only looked for AUD symptoms, or feared ruining rapport with older adults by asking about alcohol use, were reluctant or refused to implement prevention interventions.60,130-132 Providers also reported low motivation to screen due to limited time and little training to respond to positive screens.60,129-132 From their perspective, older adults reported feeling that providers did not want to hear about or treat drinking,128,129 that the topic was too personal to broach,17,128 or that the provider was too young to understand.20 When older adults perceived interventions to be irrelevant to their situation or misaligned with their preferences or circumstances, they were reluctant to or incapable of changing alcohol use before resolving their stress and mental health problems.17,63,133-135

Potential Barriers to Successful Prevention Interventions Among Older Adults

- No third-party reimbursement for intervention60,66

- Cost and availability of staff to implement65,128

- Cost and availability of additional help65,128

- Low readiness to include regular screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) or other screening65

- Low commitment to implement SBIRT or other screening65

- High staff turnover65

- Lack of resources (e.g., space, administrative support)65

- Contractual agreements that inherently discourage assessment129

- No on-site champions for screening and interventions, leadership65

- Set in acute care settings where other health problems may be priority75,77

- Too general or too many target behaviors67,71,72

- Too passive (e.g., a letter with results for seemingly unrelated health problem)73

- Unverified or low exposure to intervention26,73,88,91,92,97,104,125

- Definition of standard drink without visual or experiential learning that does not hold20,128

- Perceptions of Older Adults

- Older adults don't drink130

- Alcohol is permanently entrenched in life, no possibility of change130

- No insight among older adults, in denial, health illiteracy60,130

- Older adults are fragile, fear of being insensitive or ruining rapport60,130,131

- Right to self determination130

- Alcohol Only Needs to Be Focus of Concern When

- Risk of harm in home environment (e.g., fire)130,131

- There are alcohol use disorder symptoms present130,131

- Low Motivation to Screen

- Need to prioritize other chronic conditions130,131

- Inadequate training, support and/or place to refer older adults to for specialized treatment60,129,130

- Too busy, too little time, not interested129,132

- Low job satisfaction to screen or treat129

- Can’t directly observe improved quality of life of the older adults130

- Experience in Health Settings in General

- Perceive primary care provider as not wanting to treat drinking; drinking is not legitimate issue to bring up128,129

- Discomfort, embarrassment, feels too personal to discuss with primary care provider17,128

- Provider is too young, won’t understand20

- Self-Perception, Preferences, and Experience Misaligned with Intervention

- Considers themselves as drinking responsibly, no need to change, regardless of risk information133,134

- Consider themselves wiser due to age, can handle drinking134

- Alcohol-related health salience (no apparent consequences, no change)17,134,135

- Doesn’t consider information relevant, even if it includes their age group60,128,133,136

- Believability of the education/feedback (doubt its veracity, not convinced)63,128,129,133,136

- Feel pushed, preached to128

- Does not want to be abstinent, prefers moderation17

- Physical/mental health problems are more urgent, wants to treat those first133

Conversely, numerous attributes can enhance the success of prevention interventions (see the box “Facilitators to Successful Prevention Interventions Among Older Adults”). Primary prevention interventions implemented where older adults are waiting and otherwise unoccupied (e.g., waiting room, pharmacy, hospital atrium) provided opportunities to engage older adults and were acceptable across generation and sex.20,54,59-61,70 Flexibility of place, timing, and frequency of contact,20 such as including grocery stores, in-home visits, or other places older adults routinely visit (and outside an acute care setting), can better capture older adults’ attention and provide access to brief interventions for older adults. Playful activities, such as gamification of prevention interventions,56 may also engage older adults more effectively by broadening education and screening, normalizing alcohol conversations, and reducing stigma.127 Steps taken to increase trust in information provided to older adults, such as using established and trustworthy sources that also illustrated the relevance of information to their level of risk and perceived concern, appeared to better engage older adults in evaluating their drinking and planning for change.63,79,128,129,133,136,137 In primary care settings, prevention intervention components effective across generations included onsite behavioral health services, 90 drink tracking,45,96,97,99,100,102 agreements with another person to reduce drinking,96,97,99,100,102 normative and/or personalized feedback,63 full dosage of intervention,97 and follow-up visits or calls with providers or peers over months for further support and/or accountability. Physician involvement69,96,98-100,102,125,138 appeared crucial for older generations (GG/TSG), whereas provider profession appeared less pivotal for younger cohorts. Studies in which both physician and patient were provided with feedback were the most effective among GG/TSG older adults. Whether professionals or peers, a relaxed style of the provider that avoids interrogation and aligns the tone of feedback with the older adult’s level of concern appeared to be particularly important to engage older adults.20,46,124-127 Finally, digital interventions may attract an important subset of older adults who subsequently reduce harm.111

Facilitators to Successful Prevention Interventions Among Older Adults

- Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) as a reimbursable intervention66

- Greater societal normalization of discussing alcohol20

- Community building with alcohol-free activities and events for older adults20

- Resilience activities at the individual, small group, and wider community level20

- Places in which older adults may be waiting and available for intervention (e.g., primary care waiting rooms, pharmacy line, hospital atriums, grocery stores)20,54,59,70,127

- Part of a Medicare annual wellness visit67

- Flexibility in terms of time, location, and frequency of contact127

- Nonstigmatizing settings, including in home22,23,110,123,126

- Group education (also provides community as a protective factor)20,53,56,57

- Gamification56

- Variety of educational mediums, posters, brochures, and public service announcements57,127

- Sustained education over time (repetition, reminders, booster sessions)20

- Inclusion of citations of facts to increase trust in the information63,79,128,129,133,136,137

- Normative feedback, especially for older men79,103

- Personalized feedback, especially for older women28,57,70,81,82,110

- Gamification56,76,83

- A variety of messaging approaches (i.e., not only health-based messages)68

- Eliciting active engagement, not just passive information83,111

- Inclusion of citations of facts to increase trust in the information63,79,128,129,133,136,137

- Assessment and feedback using the AUDIT, AUDIT-C, ARPS, or the CARET22,23,55,65,66,70,82,84,96,97,99,104,108,109,112

- Physician provides feedback and is part of agreement to reduce drinking69,96,98-100,102,125,138

- Both physician and patient receive feedback69,70,96,98-100,102,138

- Printed materials, detailed booklet54,70

- Personalized and normative feedback55,58,63,70

- Drink tracking, daily diary45,96,97,99,100,102

- Agreement to reduce drinking, commitment, accountability96,97,99,100,102

- Age-specific and awareness of relevance to specific participant53,57,60,127,128,133,136

- Human contact (peers, providers, small groups)57,135

- Encouraging older adults to both provide and receive help57,127

- Motivational interviewing and/or cognitive behavioral therapy22,23,81,82,94,96,97

- Multiple points of contact over time96,97,99

- Easy relaxed style20

- Avoids interrogation20

- Aligns feedback tone with older adults’ level of concern for alcohol use20

- Long established relationships with older adults (particularly for African Americans)65,150

- Nonmedical providers (younger and African American older adults)65,150

Studies also identified several factors that motivate older adults to sustain or change drinking behavior (see the box “Reasons to Change or Sustain Drinking Among Older Adults”). Like adults across the life span, older adults reported taking pleasure in the ritual of drinking, that drinking adds to their quality of life and socialization, and that it provides relaxation.128,134 Pleasurable factors potentially unique to older adults were that it is one last pleasure in their lives, connects them to their youth, and makes them feel enjoyably rebellious.127,128,134 Older adults also reported using alcohol to escape or cope with distress related to loss, illness, or lack of purpose, and in some cases as a form of “medicine” to treat pain, reduce stress, and aid sleep.128,133-135,139 Older adults reported a willingness to change when it leads to tangible benefits, such as seeing family or travel;128,139 to avoid negative consequences and stigma;20,134,135,139 or when there was a change in their life circumstance that may require change, such as lack of money or presence of a homecare worker who is monitoring drinking.134,140

Reasons to Change or Sustain Drinking Among Older Adults

- Aspects that Older Adults Specifically Report as Rewarding

- “The ritual”44,64

- Adds to quality of life, relaxation128,134,139

- Important part of later life, last pleasure44,64

- Part of identity as fun, connected to youth44,64

- The rebellious feeling that comes with drinking108

- Part of Socialization128,134

- Meaningful part of time with friends128,134,139,152

- Meaningful part of time with spouse or partner139

- Cultural norms with family and friends, expectation of drinking134

- Occurs in settings where there are adverse social consequences for not drinking (e.g., in retirement community)128,134

- With meals and on special occasions128,134

- Often in settings with an abundance of alcohol where socializing128,134

- Motivation for Drinking

- Marks the structure of the day134

- Coping

- Coping with loss, bereavement128,134

- Coping with illness or cancer (hopelessness)128

- Coping with loss of purpose127

- Among men, used to hide degeneration due to aging128

- “Form of medicine”128,133-135,139

- Treats pain133

- Sleep aid134

- Positive effects on health and well-being128,134,135

- Reduces stress133,139

- No Benefits to Reducing Drinking

- Optimistic bias: no problems yet; won't affect me128,134,152

- Perceive little risk, view self as controlled, no need to reduce128,134

- Perceive little benefit from acting on risk information133,135

- Habit, perhaps too difficult to break128

- To Optimize Life

- To be able to see and spend time with grandchildren, family commitments128,139

- To be able to travel128

- Part of a positive view of aging152

- To Avoid Negative Consequences

- Hangovers, blackouts134,139

- Medication interactions20

- Avoid drunk driving128,134,135

- Avoid ill health128,135,140

- Fear of falling, looking foolish128

- Stigma of Heavy Drinking128,134

- Particularly for women110,128,134,135

- Religious/cultural beliefs20,128,134

- Change in Life Circumstance

- Not going out as much140

- Don't have money140

- Trying to lose/control weight128,135

- Not able to drink as much due to age128

- Doctor gave me advice to reduce128

- Homecare workers encourage not drinking128

- If became ill, would reduce139

Discussion

This narrative review described primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohol prevention interventions with older adults, the barriers and facilitators to those interventions, and the impact of age, period, and generation. Like prior reviews,24,26,28 design issues and vague intervention descriptions inhibit definitive conclusions. Because this narrative review compared findings across heterogenous study designs, conclusions are inherently limited. In aggregate, however, it identified consistent aspects of successful prevention interventions among older adults and helped to identify gaps in the literature not previously reported.

Importance of Assessment

The high prevalence of null findings of prevention interventions compared to assessment suggests there was a therapeutic effect of screening alone, particularly when the AUDIT, AUDIT-C, ARPS, or CARET were used.22,23,55,65,66,70,82,84,96,97,99,104,108,109,112 The AUDIT-C focuses on drinking quantity and frequency and, like drink tracking, may raise awareness of alcohol use. The AUDIT, ARPS, and CARET identify alcohol problems, and the older adult-specific ARPS and CARET also bring to light complexities of comorbidity, offering unique opportunities for reflection. Assessment is clearly an instrumental first pass at prevention, and experiential exercises that accompany such assessment, such as asking older adults to pour their usual drink to determine its equivalent in standard drinks,20,127 are likely impactful across generations.

Outcomes Across Generations

Alcohol-related targets, such as planning for change, treatment engagement, and treatment completion, were successfully achieved across modalities and levels of intervention intensity. However, the specific quantity and frequency of alcohol use was more immovable, with a few studies demonstrating that a notable proportion of participants continued to drink at at-risk levels. Older generations demonstrated larger reductions in drinking across prevention interventions and decade of age, yet as BB individuals aged and were included in studies, effects appeared muted. For example, only three out of 18 RCTs including BB participants identified significant findings with this group (see Table 2). This does not suggest that BB older adults do not demonstrate therapeutic benefits from prevention intervention. Rather, few studies were able to demonstrate intervention superiority to a control or an active comparison group, and effects among BB participants appear smaller in magnitude than among prior generations. That said, conclusions made about the influence of age, period, and generation should be interpreted with caution, as they are difficult to parse out. It could be that in this era of limitless options for consuming information, educational messages and interventions are simply not able to make the impact they did with earlier generations.

Aspects of Successful Prevention Interventions