This article reviews literature aiming to explain the widespread reductions in binge and problem drinking that begin around the transition to young adulthood (i.e., “maturing out”). Whereas most existing literature on maturing out emphasizes contextual effects of transitions into adult roles and responsibilities, this article also reviews recent work demonstrating further effects of young adult personality maturation. As possible mechanisms of naturally occurring desistance, these processes could inform both public health and clinical interventions aimed at spurring similar types of drinking-related behavior change. This article also draws attention to evidence that the normative trend of age-related reductions in problem drinking extends well beyond young adulthood. Specific factors that may be particularly relevant to problem drinking desistance in these later periods are considered within a broader lifespan-developmental framework.

Binge drinking is strikingly prevalent in the United States. An estimated 66.7 million (24.9 percent) of Americans age 12 or older report binge drinking in the past month, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ] 2016). This estimate is based on a binge-drinking definition of 4 or more drinks on the same occasion for women, and 5 or more drinks on the same occasion for men, on at least 1 day in the last 30 days (see sidebar, “Drinking Patterns and Their Definitions,” in this issue for a review of binge-drinking definitions). In addition to high binge-drinking rates, alcohol use disorder (AUD) is among the most prevalent mental health disorders in the United States. An estimated 15.7 million (5.9 percent) of Americans age 12 or older have a past-year AUD diagnosis (CBHSQ 2016). These rates are a public health concern, as problem drinking in the United States costs an estimated $249 billion per year (Sacks et al. 2015) and is the fourth leading cause of preventable mortality (Stahre et al. 2014).

Perhaps the most striking demographic feature of problem drinking (and various other risky or deviant behaviors) is its nonlinear association with age, characterized by increases during adolescence, peaks around ages 18–22, and reductions beginning in the mid-20s (for a review, see Jackson and Sartor 2016). However, studies showing age differences in drinking-related rates for epidemiologic purposes tend to contrast relatively broad age groups, and a finer-grained depiction is informative from a developmental standpoint. Figure 1 shows the results of the authors’ descriptive analyses of age-prevalence gradients for different drinking-related outcomes (and other drug-related outcomes included for contrast).

SOURCE: When reported, prevalence rates for ages 12 to 17 are based on U.S. NSDUH 2002 data (CBHSQ 2015). Prevalence rates for ages 18 to 70+ are based on U.S. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) 2001–2002 data (Grant et al. 2003). NOTE: Binge drinking was defined as 4 or more drinks on 1 occasion for females and 5 or more drinks on 1 occasion for males. Disorder rates reflect DSM-IV abuse or dependence except for nicotine disorder, which reflects DSM-IV nicotine dependence.

As shown in figure 1, prevalence rates for a variety of drinking-related outcomes peak in the early 20s. Specifically, in the early 20s, past-year binge drinking and intoxication rates both reach peaks of around 45 percent, and past-year AUD rates reach a peak of 19 percent. Although not depicted, similar drinking-related peaks are observed for college students and their non-college-student peers (Johnston et al. 2015), suggesting the peaks are at least partially driven by more general mechanisms beyond college attendance. Regarding historic trends, drinking-related declines have been observed across adolescent cohorts in recent years. For instance, 12th-grade rates of past-2-week binge drinking decreased from a peak of 32 percent in 1998 to an historic low of 17 percent in 2015 (Miech et al. 2015). However, college students and young adults have had far more modest cohort declines in binge drinking (i.e., from a 39-percent peak in 2008 to 32 percent in 2015 for college students, and from a 41-percent peak in 1997 to 32 percent in 2015) (Miech et al. 2015). Similar conclusions regarding historic changes across adolescent and young-adult cohorts can be drawn from NSDUH data on AUD (CBHSQ 2015).

Figure 1 also shows that, following peak prevalences in the early 20s, reliable age-related reductions in a variety of drinking-related outcomes occur beginning in the mid-20s and continuing throughout the remainder of the lifespan. For instance, after the peak binge-drinking rate of 45 percent in the early 20s, the rate declines to 38 percent by the late 20s, 29 percent by the late 30s, 22 percent by the late 40s, and 14 percent by the late 50s. For AUD, reductions appear especially dramatic in young adulthood. Specifically, after peaking at 19 percent in the early 20s, the rate decreases rapidly to 13 percent by the late 20s, then more gradually to 10 percent by the late 30s, 8 percent by the late 40s, and 3 percent by the late 50s. Of course, such cross-sectional age differences must be interpreted with caution, as differential mortality of problem drinkers and secular changes in prevalence rates could artifactually create the appearance of a developmental age gradient. However, it is unlikely that such factors could plausibly explain the magnitude of the rate changes with age, given the somewhat limited extent of overall mortality and secular variation. Further, researchers have also observed the age-prevalence curve in a number of longitudinal studies assessing how prevalence rates change as a cohort ages (e.g., Chen and Jacobson 2012).

This robust age-prevalence curve motivates and informs the conceptualization of problem drinking from a developmental-psychopathology standpoint (Sher and Gotham 1999; Sher et al. 2005). Other articles in this special issue describe factors contributing to the escalation and eventual peak of problem drinking leading up to the early 20s. This article focuses on factors contributing to the later trends toward problem-drinking reductions beginning around young adulthood.

Maturing Out of Problem Drinking

The dramatic age-related reductions in problem drinking that begin in young adulthood have motivated empirical efforts to understand desistance from a developmental perspective. Despite the overall trend toward maturing out after young adulthood, a substantial subset of individuals show persistent or escalating problem drinking beyond this developmental period (Sher et al. 2011). Knowledge of what differentiates developmentally limited versus persistent patterns of problem drinking can help clarify the nature of problem drinking and inform public health and clinical interventions (NIAAA 2008). Indeed, in addition to the above evidence that maturing out can include desistance of syndromal AUD, research also suggests that problem-drinking reductions during young adulthood are particularly likely to occur among those who were relatively severe problem drinkers prior to this developmental period (Jackson et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2013). These findings support the importance of research aimed at understanding maturing out as a means of guiding future interventions.

The following sections review evidence for different possible mechanisms of maturing out, beginning with effects of adult-role transitions (e.g., marriage, parenthood) and personality-maturation (e.g., decreased impulsivity and neuroticism) during young adulthood. Further sections then discuss the need for more lifespan-developmental research to explain the later drinking reductions observed in developmental periods beyond young adulthood, noting some mechanisms that may be particularly relevant to desistance in these periods (i.e., “natural recovery” processes, health issues). A key point pertaining to all mechanisms reviewed here is that more research is needed on possible historic changes in how these mechanisms have operated. Preliminary descriptive evidence suggests historic differences across cohorts in the age-related trend of escalation followed by maturing out (e.g., see figure 5-18d in Johnston et al. 2015). Key public policy insights could be gleaned from in-depth analyses of such cohort changes in age trends and how they may relate to cohort changes in desistance mechanisms (e.g., the prevalence, life-course timing, and impact of adult-role transitions). It is also noteworthy that evidence exists for gender, racial, and ethnic differences in both patterns and mechanisms of age-related drinking reductions (Chassin et al. 2016; Chen and Jacobson 2012; Jackson and Sartor 2016). Although discussion of such differences is largely beyond the scope of the current brief review, this should be noted as another important topic in need of further exploration in future research.

Young Adult Role Transitions and Maturing Out

The most commonly offered explanation for maturing out of problem drinking during young adulthood is that it is driven by transitions into adult roles like marriage, parenthood, and full-time employment (e.g., Bachman et al. 1997). Young adulthood is marked by widespread adoption of such roles (Bachman et al. 1997), and well-established developmental theory views these transitions as key young adult developmental tasks (Erikson 1968). Role incompatibility theory (Yamaguchi and Kandel 1985) is often referenced to explain how these roles influence maturing out. The theory holds that, when a state of conflict (i.e., incompatibility) exists between a behavior (e.g., drinking) and demands of a social role, this can initiate a process called role socialization, whereby conflict is resolved through changes in the behavior. However, the theory also posits role selection effects in the opposite direction, whereby individual characteristics and behaviors can influence the likelihood of later role adoption. These are two very different processes through which roles and drinking behaviors can become associated, so research investigating possible role socialization effects must consider role selection as an alternative explanation.

Evidence for Role Socialization

With few exceptions (Gotham et al. 1997; Overbeek et al. 2003; Vergés et al. 2012), both marriage and parenthood during young adulthood are generally predictive of later problem drinking reductions. Further, although many studies have tested only effects of either marriage or parenthood in isolation (e.g., Curran et al. 1998; Duncan et al. 2006; Fergusson et al. 2012; Gotham et al. 2003; Kendler et al. 2016; Kretsch and Harden 2014; Lee et al. 2010; Warr 1998), there is also research demonstrating that both marriage and parenthood can contribute uniquely to these reductions (Bachman et al. 1997; Little et al. 2009; Staff et al. 2010). In contrast, research has often failed to show that employment contributes to reduced problem drinking in young adulthood (e.g., Bachman et al. 1997; Gotham et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2010), although some evidence for this effect has been found within certain occupational categories (e.g., “professional” jobs) (Staff et al. 2010).

Evidence for Role Selection

Most studies have failed to show that alcohol use reduces the likelihood of young-adult marriage, parenthood, or employment (e.g., Curran et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2010), with some findings even suggesting the opposite effect (e.g., Bachman et al. 1997). However, results appear more mixed for more severe indices of problem drinking and for illicit substance use. For example, research has shown that AUD can prevent marriage and parenthood (Waldron et al. 2008, 2011) and that illicit-substance use can prevent marriage and employment (Bachman et al. 1997; Brook et al. 1999; Flora and Chassin 2005; Hoffman et al. 2007).

Practical Implications of Role Effects on Maturing Out

In addition to evidence that family roles can spur desistance from AUD (e.g. Dawson et al. 2006; Gotham et al. 2003), there is even evidence that these roles may have especially dramatic effects among those who were particularly severe problem drinkers prior to role adoption (Lee et al. 2015a). These findings support the clinical significance, not only of maturing out in general, but of role-driven pathways to maturing out in particular. Further, beyond family-role effects on drinking-related maturing out, there is mounting evidence from diverse literatures that family roles convey various protective effects that can cascade across many domains of life to broadly spur adaptation and mitigate pathology (Derrick and Leonard 2016; Roberts et al. 2006; Sampson et al. 2006; Walters 2000).

However, given the potential importance of these processes from a public health standpoint, it is surprising how little is known about the mechanisms through which roles influence substance-related maturing out. Existing mediational findings show the most robust support for mediation of role effects via reduced socializing with peers, with additional mixed evidence for mediation via changes in drinking-related attitudes and increased religiosity (Bachman et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2010; Staff et al. 2010; Warr 1998). Mediation via peer involvement is particularly consistent with the popular role- incompatibility explanation of family-role effects on maturing out (described above), as role demands may restrict socializing opportunities. However, as articulated in Platt’s (1964) commentary on how to achieve “strong inference,” future studies should conduct “riskier” tests of role incompatibility theory. This means testing hypotheses that could potentially provide discriminating support for role incompatibility theory over other plausible explanations, and testing hypotheses that could potentially disconfirm the theory in favor of other explanations. For instance, an explicit assessment of conflict between drinking and role demands (role incompatibility) could provide discriminating support for role incompatibility theory (Lee et al. 2015a), and this should be tested against other plausible mechanisms such as the interpersonal support, security, and satisfaction that family roles can provide (see Roberts and Chapman 2000).

Young Adult Personality Development and Maturing Out

A vast, longstanding literature links personality and drinking, although variability in personality models, definitions, and terminology can sometimes complicate interpretation of this work (Sher et al., in press). For instance, “Big Three” models (Tellegen 1985) of the traits that compose personality typically include constraint (related to impulsivity and risk taking), neuroticism (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress reactivity), and extraversion (e.g., sociability); whereas “Big Five” models typically include neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness (or intellect) (e.g., Costa and McCrae 1992; Goldberg 1990). Within “Big Five” models, distinct components of impulsivity and constraint (e.g., lack of perseverance, negative affect urgency) are represented as smaller facets of the larger broadband traits (e.g., conscientiousness, neuroticism) (Whiteside and Lynam 2001). It is beyond this brief review’s scope to broadly review the many ways these and other models of personality have been linked to drinking, but see Sher and colleagues (in press) for an in-depth review of personality and alcohol research.

This review focuses on one particularly relevant burgeoning area of personality research that has emphasized movement beyond a static view of personality, acknowledging that normative changes in personality occur throughout the lifespan. Importantly, findings include evidence for adaptive (i.e., presumably beneficial) changes in personality traits that have been linked closely to heavy and problematic drinking, including impulsivity, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. Further, maturational changes in these traits appear particularly rapid around the transition to young adulthood (i.e., the 20s and 30s), the period when normative age-related declines in drinking generally begin. For instance, figure 2 depicts meta-analytic evidence for age-related increases throughout the adult lifespan in both emotional stability (akin to lack of neuroticism) and conscientiousness (Roberts et al. 2006; for more on personality maturation, also see Caspi et al. 2005; Roberts et al. 2005).

SOURCE: Adapted from Roberts et al. 2006.

Correlated Change in Personality and Problem Drinking

Perhaps motivated by the above evidence for personality maturation, a subsequent series of studies has shown that the normative age-related drinking reductions of young adulthood may be partially explained by age-related personality change (Littlefield et al. 2009, 2010a). Longitudinal growth models showed a reduction in average levels of problem drinking from age 18 to 35, along with corresponding reductions in impulsivity and neuroticism and increases in conscientiousness. Further, parallel-process growth models showed correlated change such that those with greater age-related maturation in these three personality domains also had greater age-related reductions in problem drinking. A follow-up study using the same data (Littlefield et al. 2010b) also showed that age-related changes in drinking motives mediated effects of age-related personality change on age-related problem-drinking reductions. Specifically, reductions in neuroticism and impulsivity predicted reductions in coping-related drinking motives, which in turn predicted reductions in problem drinking. These are the only studies to our knowledge analyzing correlated change in personality and drinking as an explanation for the normative drinking reductions observed around the developmental transition to young adulthood (i.e., maturing out), although other studies have shown similar correlated change in earlier developmental periods of normative drinking-related escalation (i.e., adolescence to the early 20s) (e.g., Ashenhurst et al. 2015).

Directional Effects of Personality on Drinking Over the Course of Young Adulthood

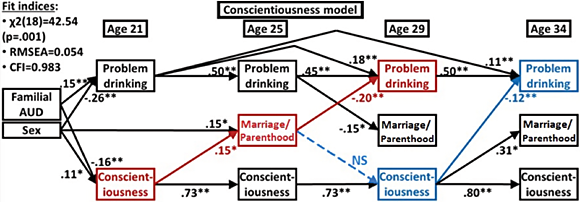

The above studies of correlated change between personality and problem drinking have forged an entirely new avenue for research on drinking-related maturing out, with one important next step being investigation of different possible directions of effects. Toward this objective, Lee and colleagues (2015b) estimated cross-lag models testing bidirectional effects between personality and problem drinking across four waves spanning ages 21 to 34. Results showed some prospective effects of personality on problem drinking, with lower impulsivity and higher conscientiousness at age 29 both predicting lower problem drinking at age 34 (see figure 3). In contrast, results did not show prospective effects of neuroticism on subsequent problem drinking (nor prospective effects in the opposite direction).

SOURCE: Figure adapted from Lee et al. 2015b.

NOTE: Colors highlight parts of the model testing hypothesized mediation paths. Red variables and paths highlight results confirming the hypothesized mediation of conscientiousness effects on problem drinking via marriage and parenthood. Blue variables and paths highlight results failing to confirm the hypothesized mediation of marriage and parenthood effects on problem drinking via conscientiousness. For marriage/parenthood, 0 = remained never married and a non-parent; 1 = became married or a parent. For family AUD: 0 = family-history negative; 1 = family-history positive. For sex: 0 = male; 1 = female. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Integrating Adult-Role and Personality Effects on Maturing Out

Beyond the largely separate bodies of evidence for family-role and personality-maturation effects on young adult drinking reductions, little work exists advancing an integrated model of these ameliorative processes. Differing views conceptualize personality maturation as unfolding either (1) due to biologically programmed maturation or (2) as an adaptive response to age-increasing contextual demands (e.g., from family roles) (Roberts et al. 2006). These alternative views imply different predictions regarding possible mediated pathways involving role and personality effects on problem-drinking reductions. To investigate these possibilities, the cross-lag models of Lee and colleagues (2015b) (discussed above) also included transitions into family roles (marriage or parenthood). Results showed that family-role transitions mediated personality effects, with higher conscientiousness and lower impulsivity at age 21 predicting transitions into a family role by age 25, which in turn predicted lower problem drinking at age 29 (see figure 3). In contrast, personality was not found to mediate role effects, as role transitions consistently failed to predict later personality (see figure 3).

Practical Implications of Personality-Development Effects on Maturing Out

The notion of interventions targeting personality change has received increased attention in recent literature (e.g., Magidson et al. 2014). The above-discussed research on personality and maturing out has especially highlighted the potential utility of reducing impulsivity and increasing conscientiousness. Littlefield and colleagues (2009) speculated that interventions fostering maturity in these domains might spur relatively durable changes in drinking behaviors. Lee and colleagues (2015b) noted, based on the above mediation findings, that pre-young-adult personality interventions could convey protective effects, in part by aiding successful transitions to family roles in young adulthood. Based on evidence for persistent effects of childhood impulsivity even on midlife outcomes, Moffitt and colleagues (2011) argued that universal prevention programs fostering childhood self-control could confer substantial and lasting benefits to most individuals and to an entire population. Indeed, early prevention and intervention programs fostering personality-related maturity could influence many etiologic pathways, thereby conveying protective effects that cascade across multiple developmental stages and domains of life.

However, to bolster confidence in the above implications, additional research is needed to confirm and further characterize the phenomenon of personality maturation and its effects on age-related drinking reductions. Caution is perhaps warranted regarding the use of survey measures to show personality change, as measurement invariance across ages can spuriously influence apparent age-related changes (Edwards and Wirth 2009). However, given the magnitude of personality change observed across the lifespan (e.g., see figure 2; Roberts et al. 2006) and its associations with changes in various life circumstances (Caspi et al. 2005), it is unlikely that this phenomenon is largely attributable to a measurement artifact. Nonetheless, confidence could be bolstered by showing this phenomenon with alternative methods. For instance, given the existence of various task-based measures of impulsivity/disinhibition (see Dick et al. 2010), a key objective should be to confirm age-related changes in these measures and their associations with age-related drinking reductions. Such research could confirm conclusions from survey findings and further inform the practical application of this work.

Further, although clear links have been established among personality maturation, adult role adoption, and drinking reductions, more work is needed to establish directionality of effects within analyses that unambiguously capture developmental change in these constructs. For instance, the cross-lagged panel study by Lee and colleagues (2015b) addressed the unknown directionality in the growth-modeling studies of Littlefield and colleagues (2009, 2010a, 2010b), but personality effects in the analyses by Lee and colleagues did not isolate influences of age-related change in personality traits. Thus, creative analytic applications are needed to combine the separate strengths of past research. This work also may require careful conceptualization of the predicted timings and durations of the developmental processes under investigation.

Maturing Out of Problem Drinking Beyond Young Adulthood

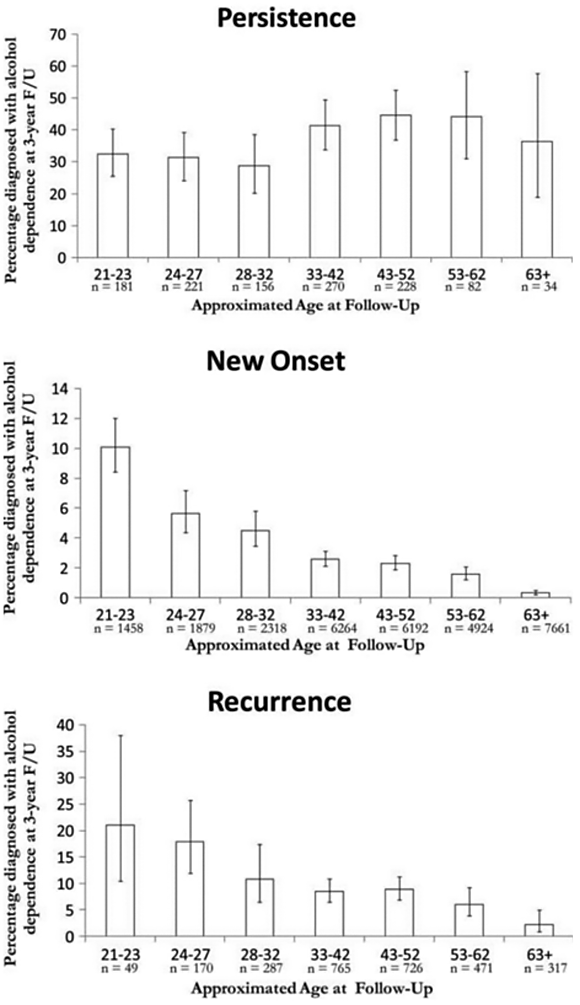

As discussed above, age-related drinking reductions are not confined to young adulthood, but instead begin in young adulthood and continue throughout the remaining lifespan. Beyond the earlier-reviewed epidemiologic evidence, some additional research offers a more precise account of changes in problem drinking across the adult lifespan. Vergés and colleagues (2012) assessed changes across the lifespan in rates of persistence, new onset, and recurrence of alcohol dependence to understand their unique contributions to overall age-related reductions in alcohol dependence rates. Results showed especially marked age reductions in new onsets (see figure 4, middle panel). Thus, although the term “maturing out” may be taken to imply age increases in desistance, the continual declines in AUD rates observed throughout the lifespan instead appear mainly attributable to reductions in new onsets. In contrast, although not emphasized by Vergés and colleagues (2012), rates of desistance appeared to peak in young adulthood. Based on persistence rates in their study, it can be inferred that the rate of desistance peaked at 72 percent by ages 28–32, then declined to a low of 55 percent by ages 43–52 and remained somewhat low thereafter (see figure 4, upper panel). Thus, an interesting possibility is that risk for AUD onset may continually decline throughout the lifespan, whereas potential for desistance from an existing AUD may peak in young adulthood. Perhaps confirming and extending the latter notion, ongoing data analyses by the authors have investigated desistance across the lifespan while differentiating among mild, moderate, and severe AUD (per DSM–5 severity-grading) (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Results showed that, for those with a severe AUD, desistance rates were substantially higher in young adulthood than in later developmental periods (e.g., severe AUD desistance rates of 46–49 percent at ages 25–34 versus 25–29 percent at ages 35–55). Of course, given that both above studies used data from the U.S. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), these analyses should be replicated in other datasets.

SOURCE: Adapted from Vergés et al. 2012.

NOTE: Persistence rate was defined as the percentage of participants with a past-year alcohol dependence diagnosis at baseline who also had a past-year alcohol dependence diagnosis at the 3-year followup. New onset rate was defined as the percentage of participant with no lifetime history of alcohol dependence at baseline who had a diagnosis of past-year alcohol dependence at the 3-year followup. Recurrence rate was defined as the percentage of participants with lifetime but not past-year alcohol dependence at baseline who had a diagnosis of past-year alcohol dependence by the 3-year followup.

The above evidence for differences across the lifespan in patterns of desistance suggests there may also be important differences across the lifespan in mechanisms of desistance. Assessing this possibility should be a key goal of future research, as researchers have clearly gleaned insights through similar attention to developmental variability in etiologic processes of earlier developmental periods (i.e., childhood and adolescence) (Chassin et al. 2013). The following sections consider some specific ways that the mechanisms influencing problem drinking desistance may vary across periods of the adult lifespan.

Maturing Out Versus Natural Recovery Models of Desistance

Predictions regarding developmental variability in desistance mechanisms can perhaps be made based on Watson and Sher’s (1998) review highlighting dramatic differences in how desistance is viewed between the “maturing out” and “natural recovery” literatures. As discussed earlier, the “maturing out” literature focuses on young adulthood and has largely viewed desistance as stemming from contextual changes in this developmental period (e.g., marriage) (Bachman et al. 1997) and accompanying role demands that conflict with alcohol involvement (Yamaguchi and Kandel 1985). Importantly, these processes are rarely conceptualized as involving acknowledgement or concern regarding one’s drinking (Jackson and Sartor 2016; Watson and Sher 1998). A starkly different view of desistance comes from the “natural recovery” literature, which has investigated precursors of desistance mostly in midlife samples (e.g., mean age = 41 [SD = 9.1] in a review by Sobell and colleagues [2000]). Informed in part by models of behavior change (e.g., Stall and Biernacki’s [1986] “stages of spontaneous remission”), this literature often views desistance as stemming from an accumulation of drinking consequences that can prompt (1) deliberate reappraisals of one’s drinking, followed by (2) self-identification as a problem drinker (i.e., problem recognition), and then (3) targeted efforts to change drinking habits (Klingemann and Sobell 2007).

Predictions can perhaps stem from an overarching premise that the maturing out and natural recovery literatures may both offer valid conceptualizations of desistance, but with maturing out models applying predominantly to young adulthood and natural recovery models applying predominantly to midlife and later developmental periods. That is, desistance in young adulthood may more often stem from the broad cascade of maturational contextual changes that occurs in this period, whereas desistance in later periods may more often stem from more direct processes of deliberate problem recognition and change efforts.

These predictions are consistent with the general idea that contextual effects are stronger earlier in development, whereas intrapersonal effects increase with age (Kendler et al. 2007) as individuals increasingly construct their own environments (Scarr and McCartney 1983). It is also noteworthy that there is conceptual similarity between the deliberate reappraisal of one’s drinking described in the natural-recovery literature and the drinking-attitude change believed to mediate personality-maturation effects on drinking-related desistance, suggesting a possible point of overlap between natural-recovery and personality-maturation research. Thus, personality maturation in young adulthood (e.g., conscientiousness increases) may distally potentiate later natural recovery processes of problem recognition and effortful change. Although quite speculative, if the above predictions are supported, this would help bridge divides among different highly influential yet ostensibly discrepant views of desistance. More generally, investigating these predictions could help advance the field toward a more unified understanding of desistance across the lifespan and thereby inform developmental tailoring of public health and clinical interventions.

Older Adult Health and Problem Drinking Desistance

Although health and drinking are of course interrelated throughout the lifespan (Knott et al. 2015; Plunk et al. 2014), older adulthood brings various health-related physical and cognitive challenges that may increase in importance as desistance mechanisms in this late developmental stage (White 2006). There is evidence that over 50 percent of U.S. seniors drink at levels deemed risky in the context of co-occurring medical conditions (Moore et al. 2006). Further, along with these health issues comes increased use of medications that could interact harmfully with alcohol, with a striking 76 percent of U.S. seniors using multiple prescription medications (Gu et al. 2010). Of the small extant literature on older adult drinking, health issues are among the most commonly reported reasons for desistance (e.g., Schutte et al. 2006). However, studies of prospective effects of health problems on drinking changes are more equivocal (e.g., Moos et al. 2010; Schutte et al. 2006), perhaps owing to the complex relevance of affect- and coping-related issues to older adult drinking (Shulte and Hser 2014). For instance, there is evidence that health problems can spur drinking reductions except among those who drink to cope, for whom health problems can have the opposite effect (Brennan et al. 2010; Moos et al. 2010).

Future studies should expand upon the relative dearth of research in this area. This work should include further study of how affect- and coping-related factors may impede adaptive responding to drinking-related health issues. Attention should also be paid to how these processes are influenced by aging-related increases in alcohol sensitivity (Dowling 2008; Heuberger 2009) and changes in social support systems (White 2006). These questions are particularly important given the increases in older adult problem drinking that are projected to coincide with the aging of the “baby boomer” generation (Han et al. 2009). Indeed, these projections suggest a great future need for research informing policy and clinical interventions for older adult problem drinkers.

Summary of Key Points

- Although a distinct peak in problem drinking rates is observed in the early 20s, the reductions that follow (i.e., “maturing out”) are not confined to the subsequent period of young adulthood. Problem-drinking reductions continue throughout all remaining stages of the adult lifespan.

- In addition to robust evidence that young-adult desistance is spurred by transitions into family roles, more recent work shows additional likely influences of developmental personality maturation. Research is needed to further clarify these ameliorative influences, the mechanisms through which they operate, and how they are interrelated. Such work may yield key practical insights that could inform the design of clinical and public health interventions.

- In contrast with developmental models of maturing out, other influential views of desistance (i.e., natural recovery models) place more emphasis on processes of problem recognition and effortful change. A lifespan developmental perspective on desistance may hold promise for reconciling these ostensibly discrepant models.

- More research is needed on health-related mechanisms of problem-drinking desistance among older adults.

Acknowledgments

Writing of this review was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants K99-AA-024236 to Dr. Lee and grants T32-AA-013526 and K05-AA-017242 to Dr. Sher.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.